The promise of a driverless future feels as though it’s just over the horizon, but as the technology matures, it is becoming increasingly clear that autonomous vehicles alone won’t solve our cities’ traffic and transit problems. While government regulators, technology companies, and urban planners debate the potential impact of driverless cars, another shift has been taking place in cities across the world, leading people to move about and experience urban environments differently than ever before.

RETHINKING HOW WE ORGANIZE OUR STREETS

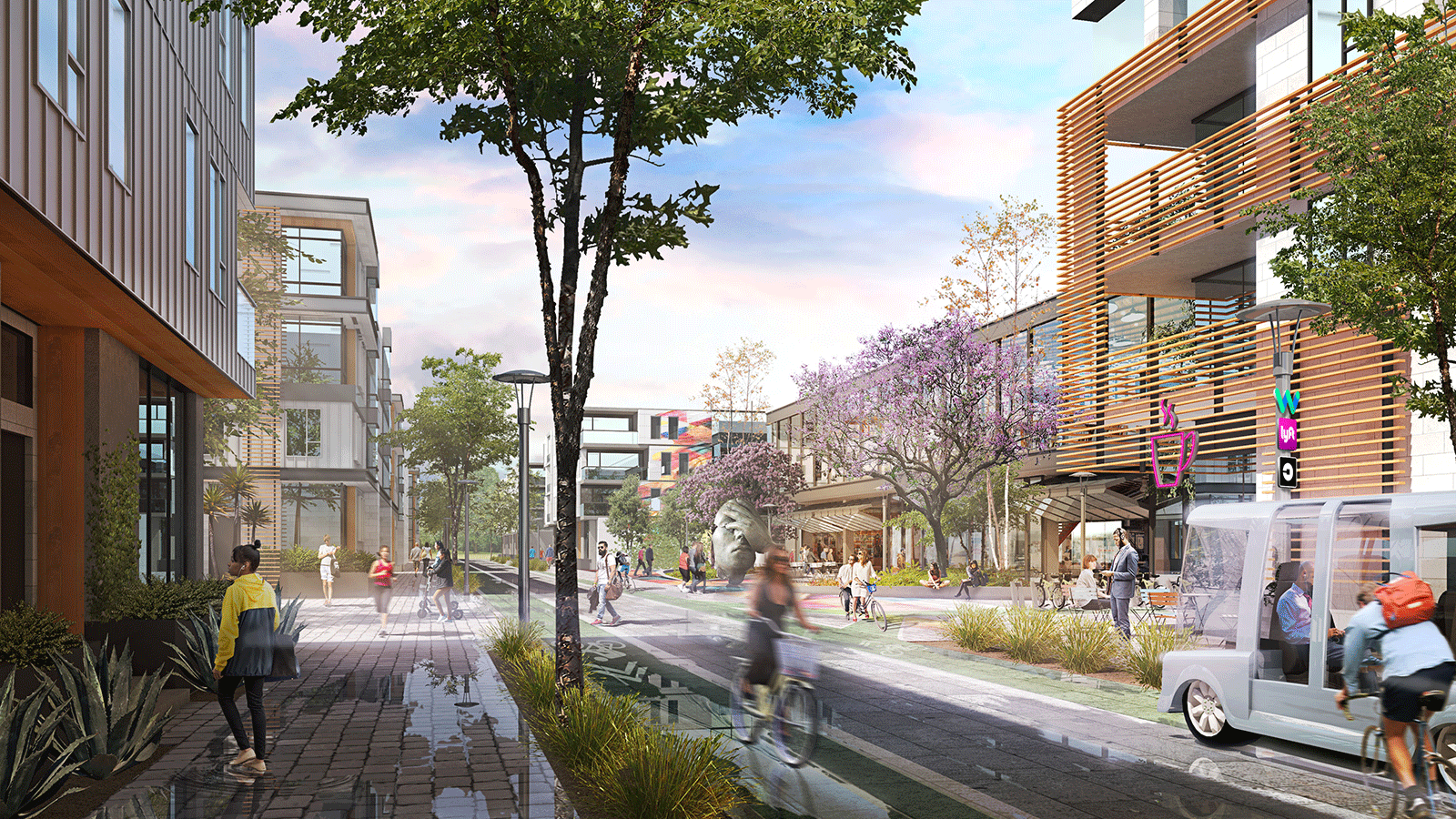

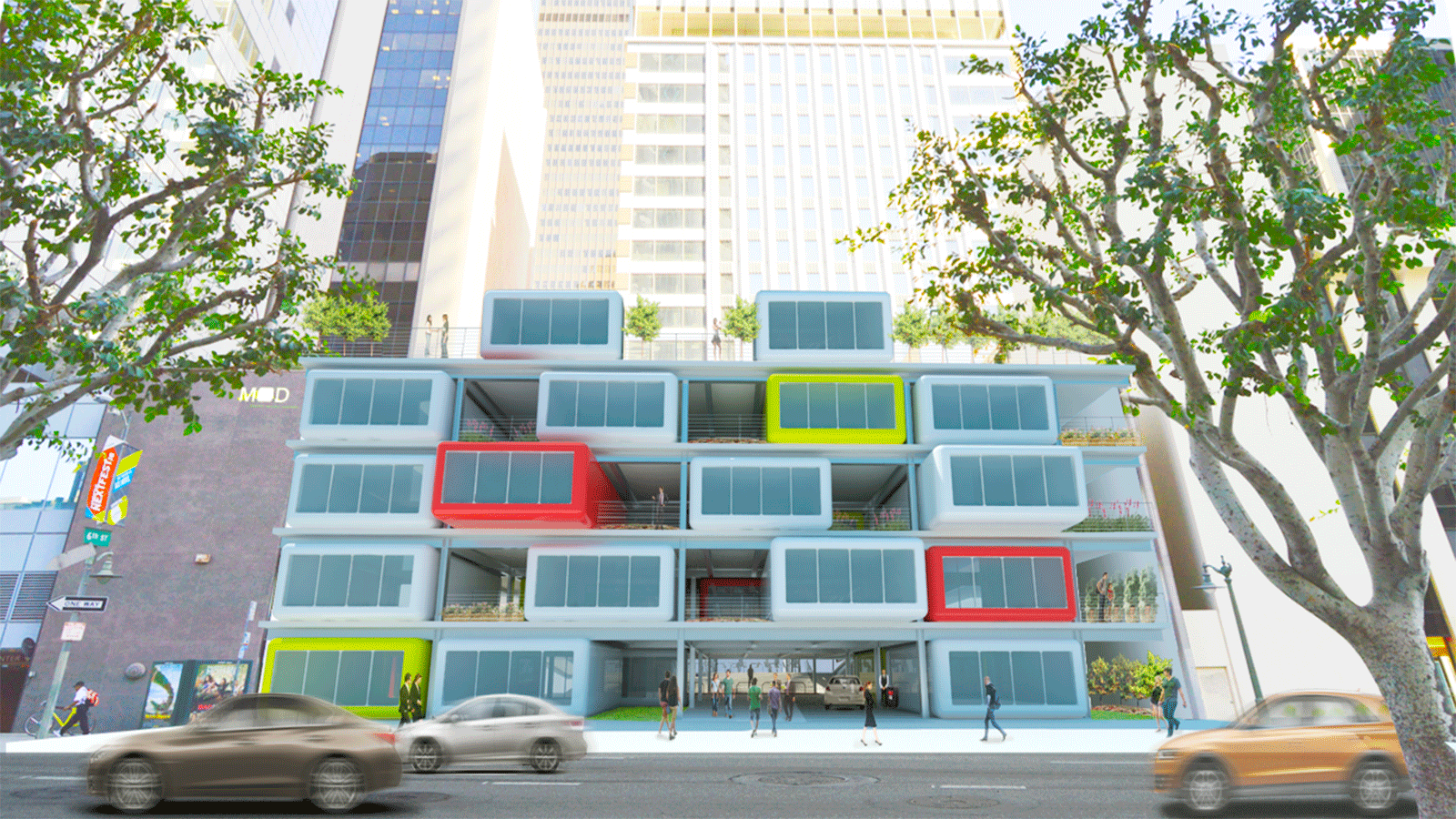

We’re entering an era where compact, mixed-use developments are the preferred places to live and work. At the same time, new modes of mobility are popping up around the globe in the form of e-bikes, electric scooters, and a host of other rolling devices. In the past year alone, hundreds of thousands of electric scooters were deployed in more than 150 cities. The number of scooter rides almost immediately eclipsed the rollout of ride-hailing services and bike shares. This potent combination of density, transit-oriented communities, and electrified mobility presents a unique opportunity to rethink how we organize our roadways and streetscapes.

BEYOND THE TWO-MODE MODE

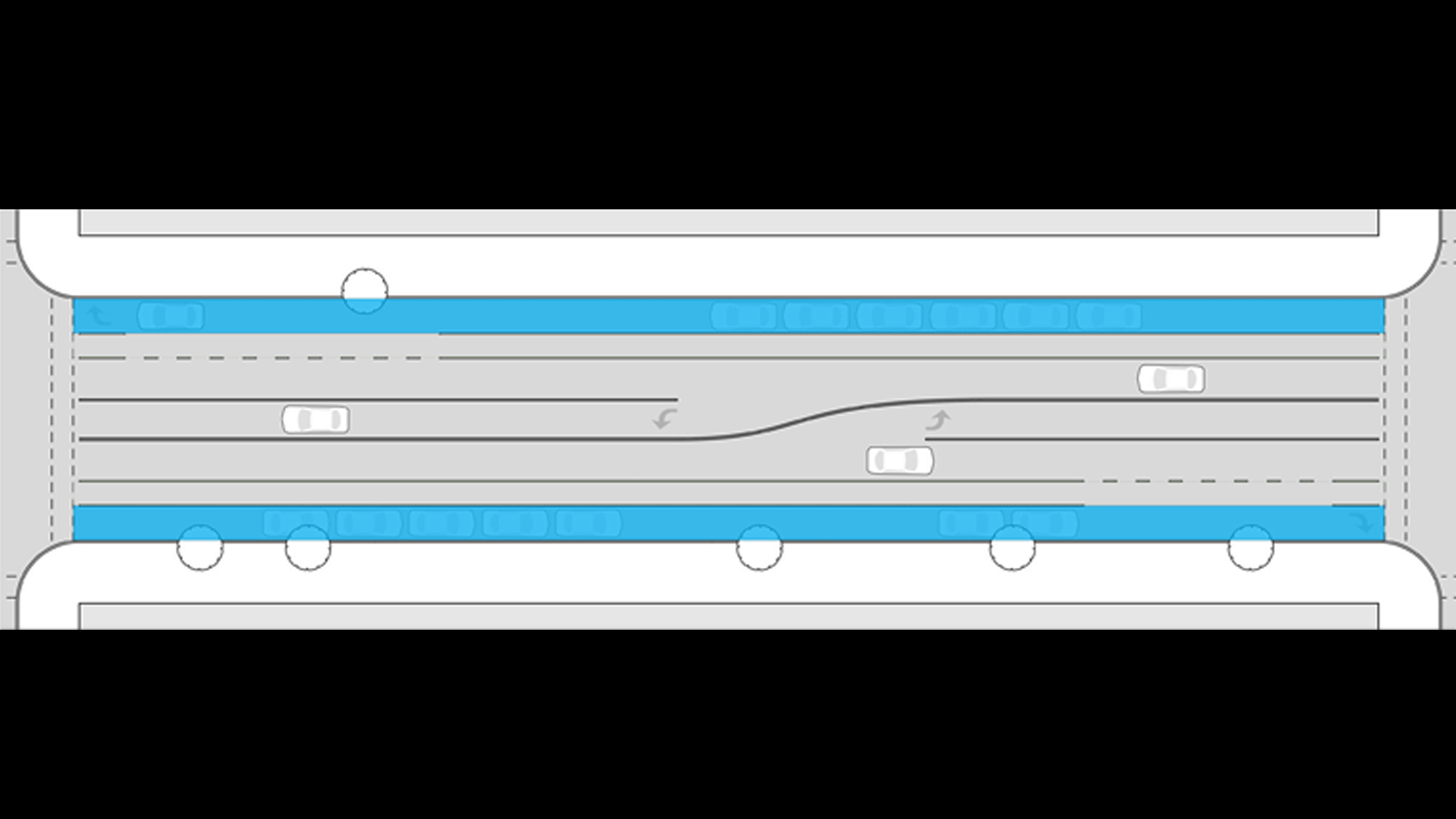

What hasn’t changed is the current balance of the roadways. Contemporary city streets were designed more than a century ago to support only two modes of mobility: primarily cars (the roadway) and secondarily pedestrians (the sidewalk). Bicycles were a third mode, and now enjoy only a modicum of space on city streets after decades of advocacy efforts.

These changes are happening amidst an even bigger psychological shift. In Europe, for example, congestion pricing and emissions charges for private vehicles have dramatically reduced use of private cars in cities like Paris and London. As citizens are forced to rethink their relationship with transportation, they begin to embrace public transit, bicycles, and other emerging forms of personal mobility. Once a critical mass of alternative transportation modes hits the streets, there’s a renewed sense that cars, trucks, and other traditional vehicles no longer own the roads.

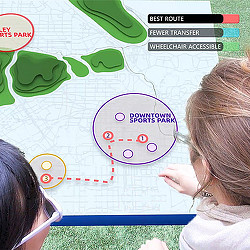

Cities desperately need an improved right of way for this emerging third group: a rolling lane for people and goods that move faster than pedestrians, but slower than cars, combined with slow speed zones where different modes can safely share streets. The meteoric rise of electric scooters is proof of a mounting desire for personal mobility as a component of dense live, work, play communities. According to research by Populus, people are willing to travel up to 3 miles on an electric scooter to access transit — versus just a half-mile on foot — making the scooter an effective tool for ushering in a new era of transit equity where automobiles are a choice, not a necessity. As planners and designers, we have a responsibility to evolve the streetscape beyond the existing two-mode model, and to ensure that some of the roadway is returned to the community in a way that works for everyone.