When Rivers Rise and Wells Run Dry: Designing Water-Resilient Cities

Climate change is making floods and droughts more intense — but designers have solutions that can limit the damage.

Flooding is one of the most visible and destructive consequences of climate change. Gensler’s most recent Climate Action Survey found that one third of people globally were recently impacted by flooding. In India, over two thirds of people report severe impacts from flooding. In the United States, damage from flooding costs an average of $4.5 billion annually. And this pressing issue is projected to intensify in both frequency and scale.

Water is overwhelming drainage systems, flowing through city streets, drowning subway systems, and sweeping away homes. Whether the cause is rising sea levels, storm surge, heavy rain, or rapid snowmelt, every type of flooding is becoming more frequent and extreme.

From Too Much Water to Too Little

On the other end of the spectrum lies drought — a slow-burn crisis that can be just as devastating as flooding. Droughts evolve over time from a lack of rain or snow, drying out soil, and preventing groundwater supplies from being replenished. These prolonged dry periods contribute to desertification, where land degrades fully and loses its ability to support life. Droughts cost Americans an average of $8.2 billion annually due to agricultural loss, reduced hydroelectric power, and, most devastatingly, wildfires.

When landscapes dry out, they become tinderboxes — turning drought into a spark for wildfires. The recent Palisades Fire in Los Angeles, which displaced approximately 150,000 people, was exacerbated by eight months of preceding drought. Unchecked urban sprawl makes wildfires worse by pushing homes and businesses into fire-prone areas, giving flames more fuel to burn and making it harder to contain the damage.

Rapid Swings Between Drought and Deluge

Floods and droughts may seem like opposite problems, but they are increasingly linked in a dangerous cycle. Like a pendulum, local climates are repeatedly swinging between too much water and too little water. A region can experience catastrophic flooding during one season and crippling drought the next. This volatile climate pattern complicates traditional water-management strategies and strains local resources.

One of the most dangerous consequences of this rapid fluctuation is the bloom and burn cycle. Heavy rains spur the rapid growth of vegetation, which then dries out during droughts, creating vast amounts of wildfire fuel. Fires strip hillsides of vegetation, making them prone to landslides when the rain returns. This destructive loop poses a considerable risk to vulnerable communities and ecosystems.

An Intensifying Crisis

This rapid swing between wet and dry conditions — what scientists call hydroclimatic whiplash — is becoming the new normal. Studies suggest that for every degree Celsius of warming, the atmosphere can hold and release about 7% more water. This amplifies both extremes of the water crisis, leading to back-to-back floods, droughts, wildfires, landslides, and even disease outbreaks.

Hydroclimate whiplash is projected to intensify most in northern Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, northern Eurasia, and across the tropical Pacific and Atlantic. Even outside these areas, all regions should expect some level of climatic shift. Both global and local strategies are needed — from international climate agreements that reduce carbon emissions to city-level resilience planning that protects communities from floods and droughts.

The Role of the Designer

Designers must move beyond seeing floods and droughts as separate hazards and instead plan for both simultaneously. As urbanists, we must design and build spaces that capture, store, and release water in rhythm with the climate — readily adapting as conditions change. Cities and buildings that are designed with water in mind are safer and more economically resilient. This design framework fosters a distinct competitive advantage, positioning more resilient places to better attract new residents and businesses.

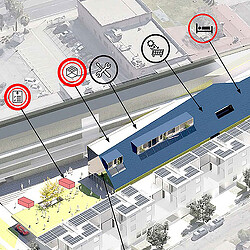

Houston offers a living laboratory for this design-first approach: Built on clay soil and threaded with bayous, it faces both deluge and drought. In response, designers are creating parks that double as retention basins, elevating transit corridors, and steering growth from high-risk zones to build resilience into the landscape and redefine how the city coexists with water.

Mexico City is another city facing a severe water shortage. Much of the water distribution network is decades old, with a staggering 40% of available water in the network lost to leaks before reaching consumers. Gensler’s proposed concept, called “Volvamos a la Fuente,” envisions a strategic plan to address water shortages in the capital with a series of rainwater catchment systems placed in neighborhoods around the city. By harnessing the power of public space design, this initiative aims to convey to communities the importance of water stewardship and highlight rainwater as a valuable resource.

Preparing for Droughts

Communities can create redundancy in water supply systems and sustain essential functions through prolonged dry periods by pursuing the following measures:

- Prioritize native and drought-tolerant landscaping

- Minimize impervious surfaces to refill groundwater

- Capture greywater for irrigation or cooling

- Incorporate aquifer recharge zones and decentralized water storage that builds long-term reserves

Designing for Water Whiplash

Navigating the swing between droughts and floods requires flexibility across infrastructure, architecture, and governance. Cities can make targeted interventions to help landscapes better absorb excess water when it is plentiful and conserve it when scarce:

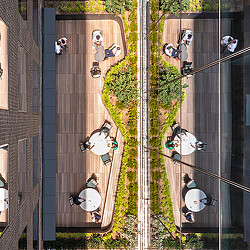

- Design parks that act as detention basins during storms

- Build shaded recreation areas for dry months

- Implement smart sensors that regulate retention, drainage, and reuse in real time

- Update zoning and building codes to encourage the design of landscapes and structures that perform under both extremes

Adapting in Coastal Areas

Finally, leaders in coastal communities can pursue the following recommendations to minimize saltwater flooding:

- Restore coastal dunes and wetlands

- Construct cut/fill canals that move water toward natural floodplains

- Divert floodwater away from freshwater supplies

- Build more permeable urban surfaces that reduce runoff

- Increase storm water storage and treatment capacity

Preparing for water volatility is one of the most pressing design challenges of our era. From how we zone land to how we detail façades, each choice at every scale shapes a city’s capacity to endure extremes. The next era of resilience will require all of us to design with water in mind.

For media inquiries, email .