Redefining Wellness in the Face of Pandemic

March 30, 2020 | By Rives Taylor

Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing exploration of how design is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At Gensler, our mission is to leverage the power of design to create a better world. At the heart of this mission is the concept of resilience, which recognizes that design must constantly evolve, adapting to and preparing for a changing world.

In the face of pandemic, we realize how essential and powerful these aims are. The COVID-19 crisis is causing us to redefine all our work around the concept of wellness and re-examine the importance of resilience. How can we better help our cities, our businesses, and our communities to better adapt and prepare for crises like these? How can our work create a better world by improving the safety, health, and experience of everyone?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This goes beyond just minimizing risk by promoting a positive state of wellness in all its forms.

In the current state of the world, Gensler is rethinking the impact of our work around three scales of wellness:

GLOBAL WELLNESSClimate change is the largest scale of impact, affecting everyone on the planet, and buildings are responsible for nearly half of the annual greenhouse emissions that have caused climate change. Last fall, we announced the Gensler Cities Climate Challenge (GC3), our plan to achieve carbon neutrality in all our work within the next decade. In recent years, we have made great strides in this direction: for example, last year our work was designed to prevent over 16 million metric tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere every year — the equivalent of taking 3.5 million cars off the road forever. By continuing our progress, we can contribute significantly to the health of the entire planet and everyone on it.

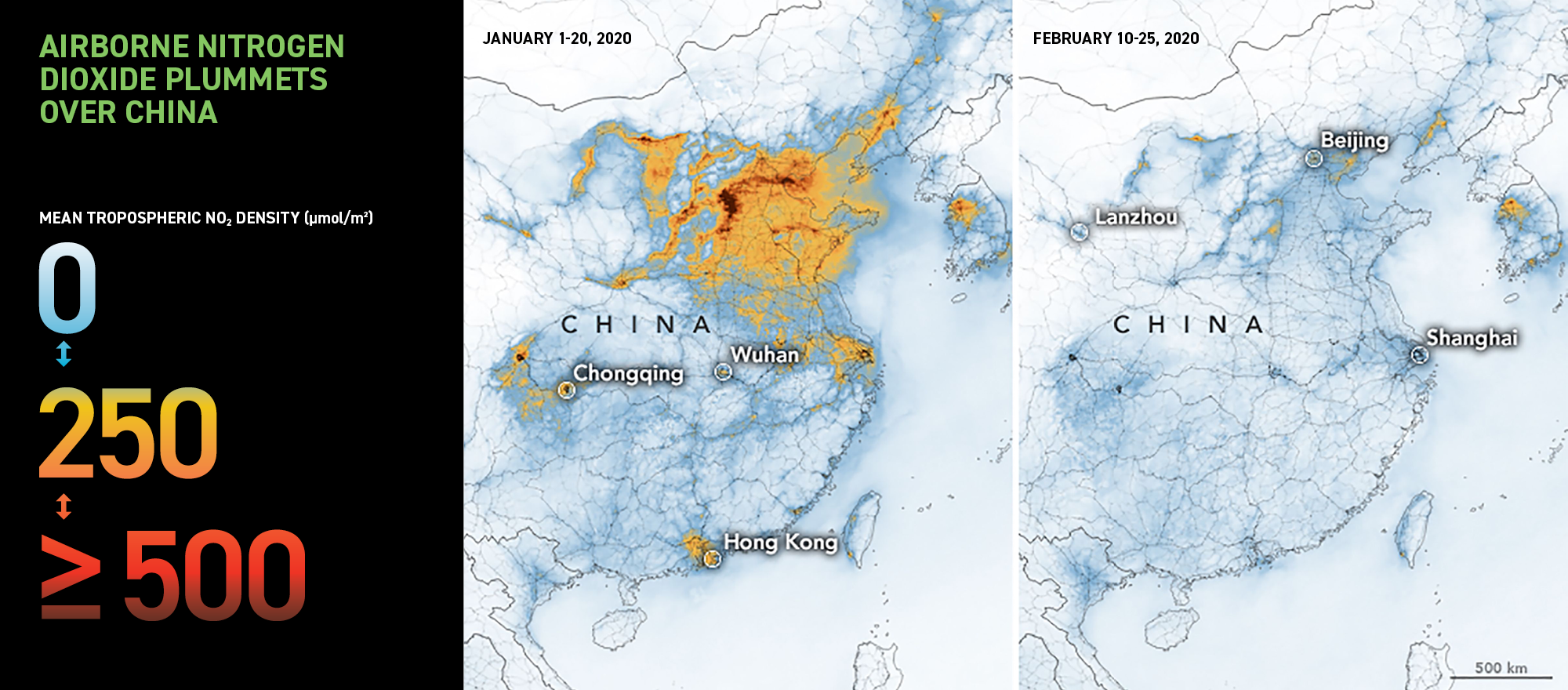

The COVID-19 crisis is severely disrupting the global economy and threatening people’s lives and livelihoods. Ironically, the virus is also having unintended benefits. After the first month of China’s downshift, its major cities showed a dramatic improvement in air quality. Satellite data has shown reductions in pollution across China, Italy, and South Korea since the outbreak started. And in car-dependent U.S. cities such as Los Angeles, traffic on roads and highways has fallen dramatically. Even if these reductions in carbon emissions rebound when people return to work, school, and travel, the short-term environmental impact that is already evident underscores the possibility — and the urgency — of taking concrete steps to make real progress toward climate action.

While shelter-in-place has been motivated by public safety, it is enhancing public health in other aspects. According to the WHO, 4.6 million people die every year from causes directly attributed to air pollution. One lesson we can take from this pandemic is that creating more walkable, dense, mixed-use cities where live, work, and play all happen in close proximity can reduce dependence on cars and curtail emissions while also strengthening local communities by creating more opportunity for social interaction and time with family.

SOCIAL WELLNESSAs of the past decade, for the first time in human history, more people live in cities than don’t. Buildings are the armature of our social interaction and more and more research demonstrates how the built environment can encourage or discourage community. What isolation is teaching us now is how important social ties are. However, this introduces a dilemma. How should we rethink cities and communal spaces in light of pandemics — to balance the need for quarantine and isolation with the need for social wellness? Now more than ever, cities can encourage more social bonding, even while facilitating physical distancing as needed. That might mean creating communal spaces of varying scales and sizes to encourage social interaction among individuals or smaller groups. Adaptability is key, and the built environment can provide a rich variety of experiences to bring people together while also keeping them safe.

Narrowly defined, public health suggests staying inside; more broadly redefined, public wellness suggests remaining connected to our neighbors. Even during the current crisis, people still need to get outdoors. Urban green spaces can improve air quality and thermal comfort at the same time, while providing proven mental and emotional benefits. The best public spaces facilitate round-the-clock enjoyment of the diversity of the urban population while allowing people to maintain reasonable distances as needed. And again, making these spaces easy to access through walking and biking can curb emissions while strengthening community. Moreover, in strongly connected communities, elderly or isolated people are less vulnerable in times of crisis.

Economic resilience is an integral part of social wellness. During the current crisis, importing and exporting goods has become challenging, a reminder that sourcing materials and products regionally can maintain a more reliable supply chain, strengthen local economies, and lower buildings’ carbon footprints by minimizing shipping distances.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, people spend 90% of their time indoors on average — and even more so during the current crisis. Over the past couple of decades, scientific evidence has increasingly revealed how buildings affect health and wellness. Good design can decrease the incidence of sickness, alleviate the symptoms of illness, and improve mental functions, outlook, and mood, resulting in dramatically better health and happiness. Buildings that promote health are critical to personal wellness. Indoor air quality, from higher outside air exchange to humidification/dehumidification set points, is becoming increasingly important, especially in dense, urban environments. We envision an integrated design partnership with our mechanical engineers, at the personal and building scale, to understand and balance costs for long-term wellness and human experience. For example, One Museum Place, an office building run by Hines that houses our Gensler Shanghai office, and the first commercial project to receive RESET™ Air pre-certification status, uses a continuous, real-time indoor air quality monitoring and management system to achieve optimal air quality. The project is setting new standards for China by ensuring year-round comfort and healthier indoor air.

In recent years, the design industry has been focused on the health impact of material ingredients, but we should be as focused on the health impact of material contact. Just this month, the threat of viral spread is teaching us much about the relationships between public space and physical touch. No one should have to worry that simply opening a door could be a health hazard. All public places can be designed so people can avoid touching surfaces and fixtures entirely. At the same time, natural materials visually convey the promise of tactile pleasure and tend to have a lower carbon footprint.

We can learn from this crisis to improve our wellness at all scales — from enhancing the experience of public spaces, to creating interiors that promote health, to strengthening our domestic supply chains. But curbing carbon emissions remains the most urgent challenge. The Earth is one, interconnected community that affects the wellness of everyone.

For any media inquiries, please email .