Security and Democracy: Designing Public Buildings for Safety and Accessibility

January 15, 2021 | By Robert A. Peck

The challenge of making public buildings safe from harm is expressed right there in the name. They are symbols of democracy and objects of pride but also, sometimes, of resentment. They attract gatherings for both civic celebrations and protests. At the same time, they are where the public’s work gets done. They must be safe, yet they must also be open for business — literally so — in a democracy in which the government serves the citizens and not the other way around.

Design has a key role to play in maintaining the balance between openness and security, in promoting both security and democratic values. Fortunately, we have learned how to design buildings that are inspiring symbols of democracy that welcome citizens as valued visitors while securing the safety of the public servants within them.

The first step in security design is assessing potential threats. Knowing what we’re guarding against will allow us to deploy the appropriate design measures and weigh costs — dollar and openness costs — in each instance. Explosive devices, active shooters, and mass protests each present different threats and call for different design countermeasures. And those countermeasures need to be integrated with security technology, engineering, and personnel training that is also tailored to the threat. In general, there are three areas to focus on when creating an open and safe civic building: defense in depth, defense in structure, and defense within.

Defense in depth: establish standoff distanceEver since the 1995 Oklahoma City federal building attack, truck bombs have been an all too familiar threat. Providing defense in depth is a particularly efficient design solution for facilities at risk of similar attacks, because the more we can keep threats at a distance from a building, the less we need to alter the building design itself.

Where feasible, providing space around our buildings aids in this effort. The farther away from a structure that an explosion occurs or that an intruder is identified and stopped, the better.

Fortunately, we can defend buildings within this “standoff distance” in a way that imperceptibly contributes to an attractive environment. Hardened and well-designed benches, fences, lampposts, signposts, and bicycle racks, along with large trees, can all serve as vehicle barriers while enhancing the public realm. Amphitheater steps, water features, and berms can provide grade changes on plazas that vehicles cannot surmount. Bollards should be the last resort, but they too should be designed to promote a sense of public dignity. Such elements can be sculptural, even whimsical, and serve their purpose.

For those especially symbolic buildings that attract mass gatherings, many of the above measures can also keep crowds at a distance and limit access to building entry points via readily controlled channels. Infrastructure embedded into the grounds can provide footings for strong temporary fencing or pop-up barriers as well as sound and video systems that in celebratory times can broadcast speeches and performances.

Defense in structure: use resilient materialsMany public buildings are embedded into street grids and fortunately so: Their very tightness to the street makes them feel like a part of the community. To the extent they are subject to credible threats and do not have an established standoff distance, we need to engineer the structural systems, facades, and windows to withstand explosive or ballistic attack. Rooftops seldom receive close design attention, but that should change to make sure our buildings have no soft spots. Fortunately, while such measures can add a marginal cost to construction, they do not significantly limit contemporary design aesthetics.

Moreover, many of these building system considerations will make our buildings more resilient against severe weather events. They also anticipate a threat that is still nascent: drone technology.

Defense within: separate employees and visitorsIn the buildings themselves, we have our last lines of defense. It is here that we must grapple with some of the most persistent modern threats: active shooters and nonviolent security breaches that could jeopardize classified or proprietary information. Entry points should be as few as possible, with separate entries for cleared employees and visitors. If possible, visitor entries should be in pavilions outside the building envelope, and designed both speed screening while also prohibiting access to the interior before screening is complete.

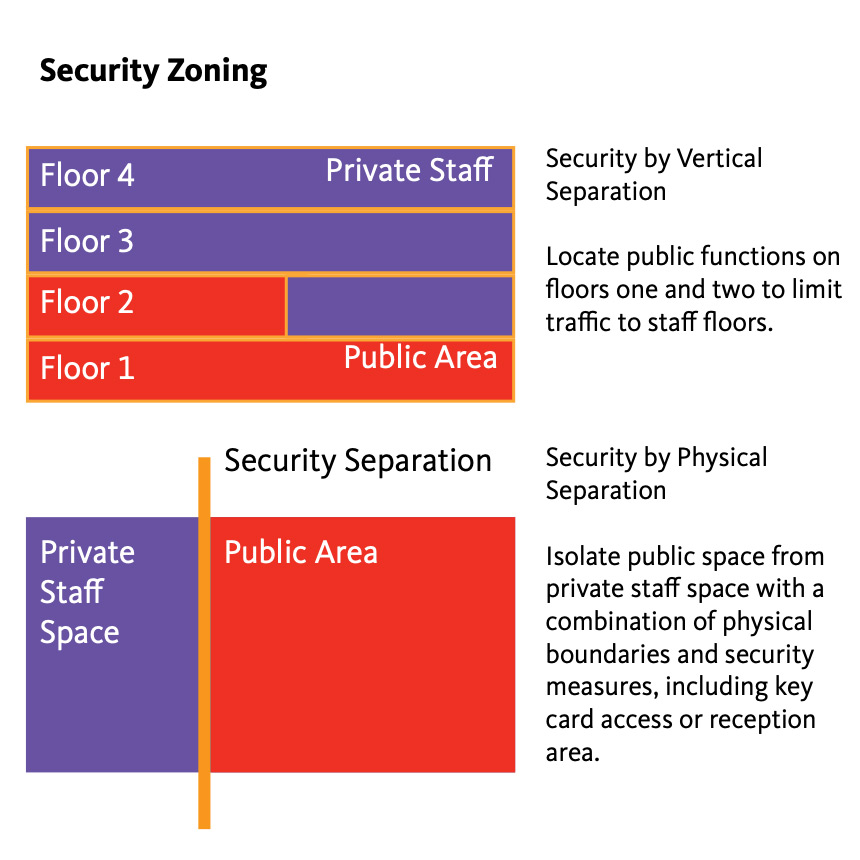

Inside, we can provide security best by separating visitor areas from employee areas horizontally, vertically, or both. The goal is to welcome citizens and unobtrusively limit access to non-visitor areas. High attendance citizen services should be grouped on the entry level, with employees traveling from their work areas to the service area. Service areas should be well-lit and comfortable, designed after hospitality settings. Access to the remainder of the building should be limited by elevator, door, and stairway entries controlled by card readers.

On any floor where visitors are welcomed, reception and visitor meeting areas should be placed as close to elevators or stairways as possible, with access to work areas on the same floor also controlled by card reader. If the threat assessment warrants, drop-down or sliding corridor and open stair barriers can be installed and activated in an emergency.

What comes next?The events of January 6th at the U.S. Capitol have called to mind again Oklahoma City and September 11th, 2001. We have been reminded that public buildings have no choice but to respond to proven threats and anticipate new ones. In the coming months and years, the biggest challenge may be assessing tradeoffs, distinguishing between threats that are more or less likely while wrestling with finite budgets and balancing security and openness.

Still, our goal above all must be to keep our public buildings public, not to close them off from the people they serve. We have the kit of design tools we need to do that. Let’s be sure we use them.

For media inquiries, email .