When the Commute Is Worth the Carbon

Where we work affects our carbon footprints — and the commute itself may have a smaller impact than many assume.

Since the pandemic’s early days, when global cities paused and remote work became widespread, the discussion on returning to the office has persisted. Now, over three years later, with offices reopened to varying degrees, the debate continues.

The Gensler Research Institute has consistently studied the pandemic’s impact on work, revealing a persistent concern for organizations and cities: the commute.

Many workers, when asked about what they missed least about going to work, cited the commute. This interstitial space between work and home became less significant as remote work became the norm. Today, the commute remains a significant barrier to higher office attendance. Workers believe they should be in the office three or more days per week for maximum productivity, yet actual attendance hovers around 50%.

The commute has attracted attention not only from workers but also from those focused on environmental sustainability. Recent studies suggest up to a 54% decrease in carbon emissions by increasing remote work, saving emissions associated with commuting and office use. Prior research by the International Energy Agency (IEA) reached a similar conclusion.

These studies are, of course, right in one regard — commuting emits carbon, particularly if going to work means driving a gas-powered vehicle.

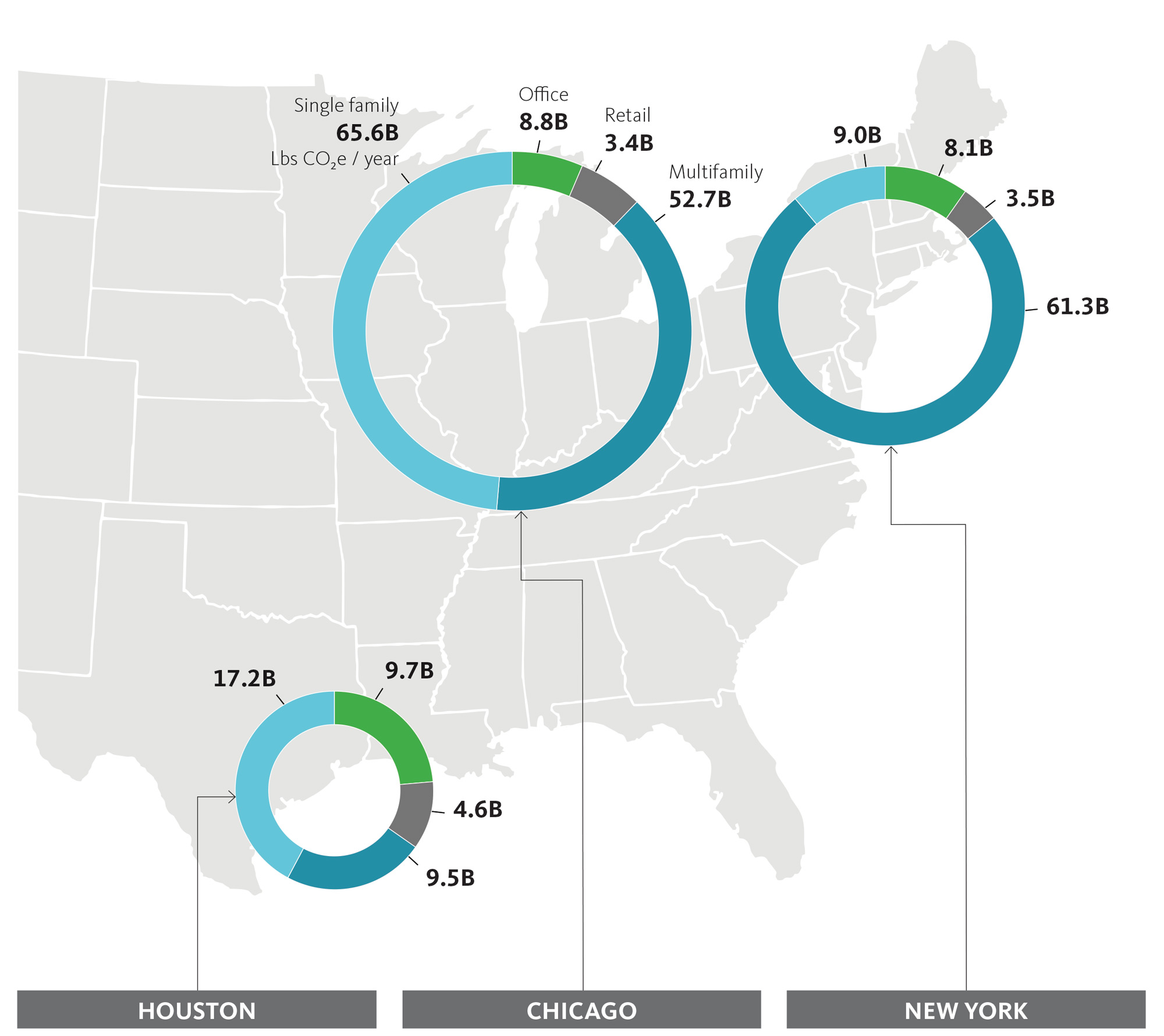

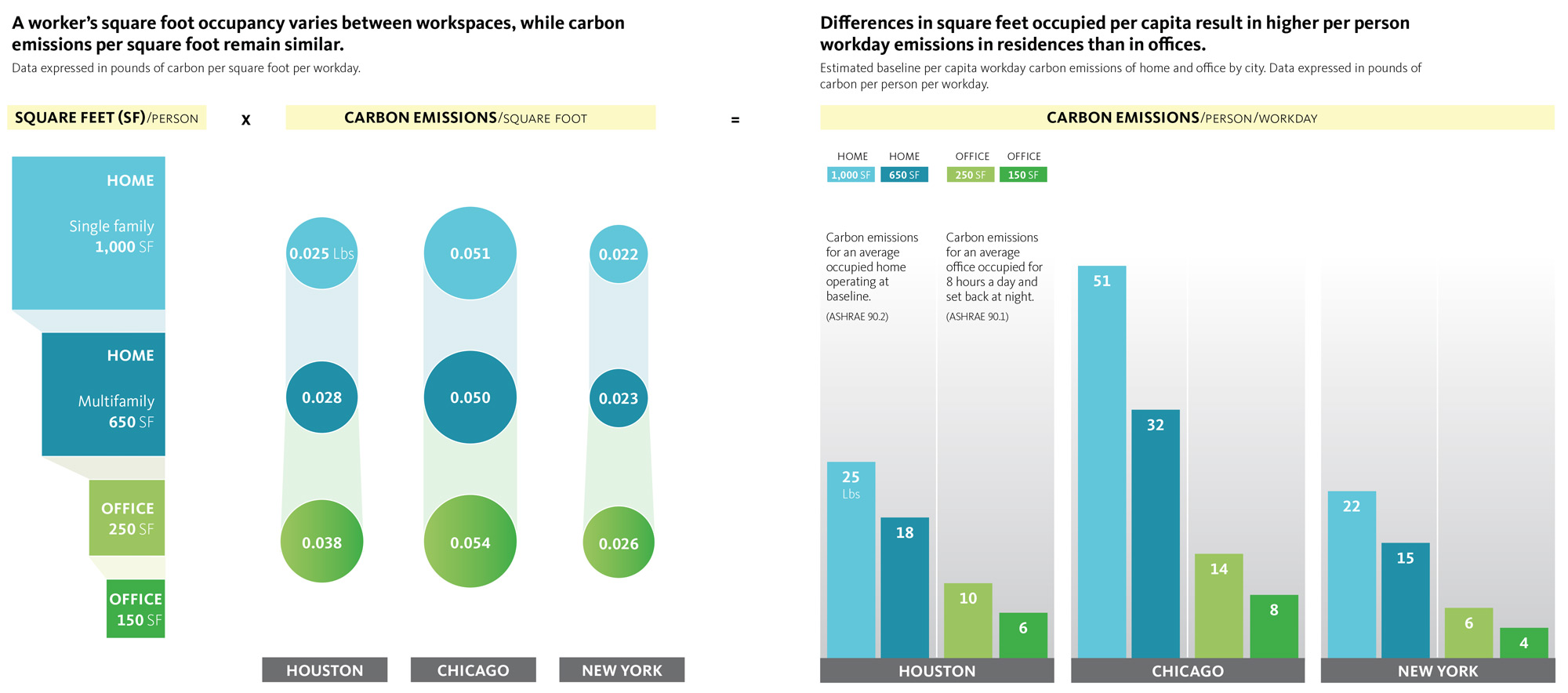

Still, the most significant workday contributor to carbon emissions is buildings, through the energy used to operate devices and condition our living and working spaces. A pilot analysis by the Gensler Research Institute that studied the carbon intensity of home and office work discovered that that the carbon emissions from the commute may matter less than we think.

The missing piece in the discussion equation is our homes. A significant portion of a city’s square footage is residential, and conditioning these homes during the workday emits mass amounts of carbon. Proponents of remote work tend to focus on reduced commuting and office emissions as a win-win, but our homes are not a fixed cost.

Setting a home’s thermostat into a wider temperature range during the day can reduce energy usage by 30%; turning the thermostat off if the space is entirely unoccupied can reduce energy usage by 60%. A reduction of that scale, for many, would save more carbon than the added emissions of both commuting and working from an office.

Reducing home energy use during the workday can offset considerable emissions, potentially saving more carbon than the added emissions of commuting and working in an office.

Taken by itself, a full office is far more energy efficient than the home. This is largely because of the square footage occupied per person. The average person working from home requires between 650-1,000 square feet of conditioned space. Comparatively, office workers require only 150-250 square feet of conditioned space. This results in far less energy use per worker. Working from the office will increase carbon if emissions in each space are fixed. However, the potential for aggressive home energy use reductions during the workday makes the office the ideal location for low-carbon work.

While the return to office question is highly complex and requires considering productivity, well-being, and other key factors, it is essential to not quickly blame the commute for carbon footprints when the greatest carbon savings could come from an empty home.

For media inquiries, email .