Why Embedding Inclusive Design From Start to Finish Is Critical

February 17, 2023 | By Gail Napell, Melany Park, and Jennifer Ellis-Rosa

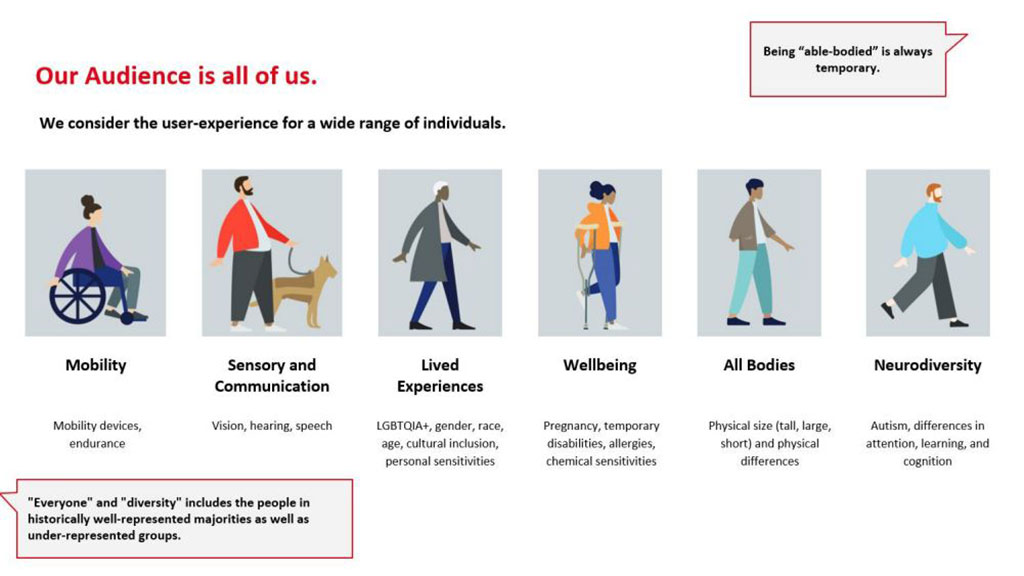

As many companies are reexamining their work environments to reflect changing business needs and shifting expectations about how their workspace is used, inclusive design is often an afterthought. But this is a critical misstep. To bring value to all users of a space, it’s vital to embed inclusivity from start to finish. In working with our workplace clients to integrate inclusive design into their spaces, we’ve used various methods, such as audits, workshops, and score cards — always folding in as many voices into the conversation as possible. From method to delivery, one thing is clear: The journey towards an inclusive design outcome must start by engaging those for whom the design is intended.

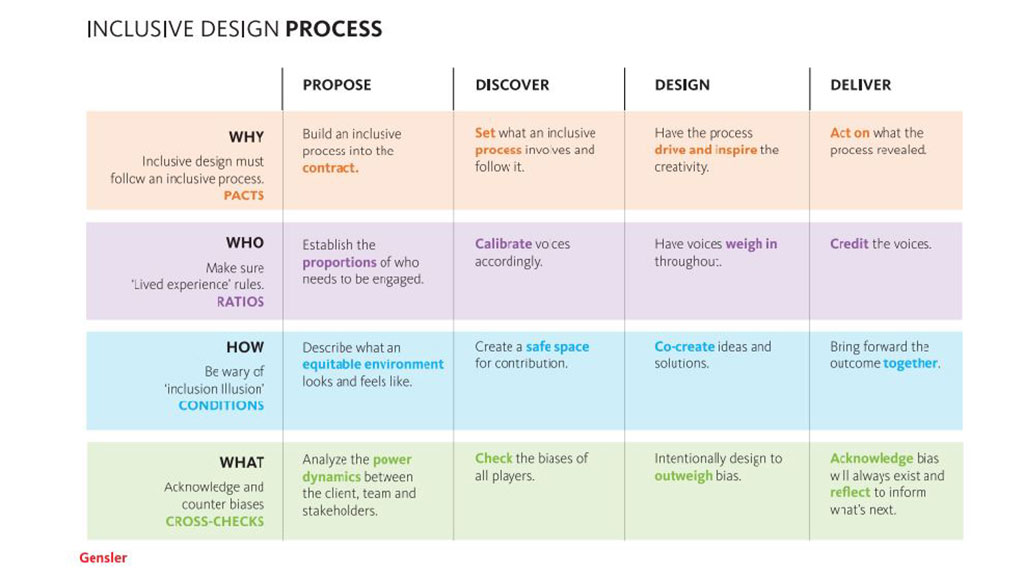

Gensler’s commitment to inclusive design continues to be a key priority in the delivery of our projects — from high-level design principles to tactical solutions we recommend to our clients. In order to deliver these inclusive design solutions, what processes and methods are required? How can these methods that get us to the inclusive design outcomes involve as many stakeholders as possible, so that the research process itself feels more inclusive and relevant?

Towards a universal process: how do we engage as many people as possible?

In 2019, the Gensler Research Institute published a report on “Achieving Inclusivity in the Design Process.” A key message of the report was that a successful inclusive design process had to gather “first-hand perspectives from people who are differently abled.” More recently, the architectural historian David Gissen has pushed this lens even further through a historical and theorical framework. In his book, “The Architecture of Disability,” Gissen argues for the embodiment of the disabled body as the driver rather than passive recipient of the urban and design experience.

What, then, can be done to translate such provocations into our design practice, so that designers engage as many voices and lived experiences as possible in the process rather than the outcome? Here are a few approaches that we’ve taken with our workplace clients that we’ve seen bring value to their employees and users of their space:

Inclusive workshops

When approaching a design project, regardless of scale, it is imperative to listen to the perspectives of employees and not just rely on leadership or design team input. To this end, inclusive workshops are an effective method through which priorities can be aligned for an inclusive experience. An inclusive workshop can be integrated early in the design process to inform design solutions or used at critical design milestones (concept, schematic design etc.) to gather experiential feedback.

In order to select a diverse set of participants, some clients have deployed a survey to gauge participant interest, while others have engaged established employee resource groups (ERGs), which are comprised of like-minded individuals who share a common characteristic or interest. The goal is to include a diverse set of participants who represent a range of abilities, gender, and race, as well as regions and culture.

An important factor to consider is the platform on which inclusive workshops are conducted. Ideally, inclusive workshops should be conducted virtually to allow individuals to participate anonymously through private messaging channels. All virtual workshop content should be accessible to people with disabilities, meaning that they need to include the following capabilities: color contrast, close captioning enabled or Alt text, and image descriptions for screen readers.

Inclusive design audit

While many workspaces are designed to meet or even exceed accessible code requirements, they often fall short of providing an inclusive experience for a diverse population. To address this, an inclusive design audit can be used to quantitatively assess the inclusivity of an office or multiple sites within a portfolio. The first step in this audit entails creating an inclusive design checklist.

The checklist, which is based on best practices, can include a methodology for ranking or rating the inclusiveness of spaces. For example, observations are one method through which spatial elements can be documented and evaluated. Audits can also be conducted virtually by reviewing design documents, construction documents, and photographs provided by the client. Importantly, clients should be engaged throughout the audit process, providing input into the design and local experience.

The inclusive design audit report ultimately delivers detailed recommendations for making improvements to each space or design detail that would otherwise hinder a holistic inclusive experience. In turn, clients can prioritize updates based on what is most important to them.

When universal means local

If the goal of inclusive design is to challenge the boundaries of what it means to be “universal” and even “inclusive,” it is critical that we reflect on the context of the decision makers who define inclusive design. Put simply, who is making the decision around what is considered inclusive in a context or geography that is not necessarily their own?

As outsiders looking in, designers and consultants must reflect on how “universal” guidelines or solutions that are intended to be as inclusive as possible may, in fact, conflict with what is culturally acceptable in the local context. In other words, a non-nuanced, decontextualized solution may problematically be more exclusive than it is inclusive. An example of this double bind is the provision of mother’s rooms, one of the most debated space types when it comes to inclusive design. While the concept is rooted in the idea that workplaces should provide working mothers a private space for lactation, its local applicability and relevance cannot be overlooked.

For instance, in countries where maternity leave is 12 months, conversations abound regarding if mother’s rooms will be used at all, and in countries like Sweden, and increasingly in the United States, a “parent’s room” is the preferred — if not mandated — nomenclature that acknowledges the different shades of parenthood.

“Nothing about us without us”

The phrase “Nothing about us without us” was first used in the English-language context by South African disability activists during the 1990s (it has an even longer lineage dating to 16th-century political traditions in Central Europe). While the term is certainly not new, the spirit of activism should still underscore the designs we put out into the world. The more we’re self-reflexive about what constitutes “inclusive design,” the more opportunity we will have as designers to activate and deliver meaningful solutions that embed inclusivity from start to finish.

For media inquiries, email .