Charting a Better Course for Senior Living

October 05, 2021 | By Tama Duffy Day

By 2060, Americans age 65 and older will number 95 million — nearly a quarter of the U.S. population. It is worth pausing on that number for a moment: nearly 100 million people, the overwhelming majority of whom will require at least some unique design considerations to age safely, happily, and purposefully in the physical environment they choose. As of today, we have not designed or built for anything close to what that will require. But it is not too late to catch up.

With 43% of surveyed older adults reporting that they feel lonely on a regular basis, we clearly have a problem on our hands. As people live longer and attitudes around aging evolve, demand for more choices is rapidly growing. Advancements in health and medicine mean that age 100 will become a more common attainment for current and future generations. If people still retire around age 65, as many will, that could leave 40 years of life for which to design.

We want those years to be imbued with activity, purpose, and interpersonal connection — which means that senior living’s future needs to be radically different. The following four principles can help us create that future, but if we want to meet the challenge of shifting demographics, the time to enact them is now.

1. Senior living should foster meaningful connections to urban life.

Gensler’s 2021 City Pulse Survey revealed something interesting: Baby Boomers are the generation that reports the highest level of satisfaction with its current living situation (66%), and the lowest interest in leaving the city where they live as a result of the ability to work remotely (24%). Stereotypes would have one believe that everyone over the age of 55 wants to pack up and move to the suburbs, but the data tells us otherwise. Vibrant urban life is desirable for everyone.

Located in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Mosaic by Willow Valley Communities is an inspiring project that cuts against the tired assumption that senior living and high-rise architecture are fundamentally incompatible. Instead, it celebrates the important role that age-qualified residents 55 and above play in the success of urban communities. It is integrated with Willow Valley Communities’ innovative Lifecare program that provides nursing, personal, and memory care should the need arise, giving residents the choice to age in place.

Mosaic is planned and designed to make residents’ connections to the urban neighborhood seamless. Here, independent living residences are spread vertically over 20 floors while a two-floor podium scaled to the neighboring urban fabric transitions the tower massing to the city itself. Communal amenities such as a club lounge with a jazz bar, ballroom, plaza garden, fitness and wellness center, spa, and tower bar are public-facing and make a 24/7 presence in the community. Willow Valley will offer memberships to the wellness center, spa, and tower bar to the public, facilitating stronger connections with the surrounding neighborhood. Retail space will be occupied by a local French bakery and coffee shop providing a taste of Lancaster’s vibrant food scene.

2. We should demand inclusive design as a baseline for every project.

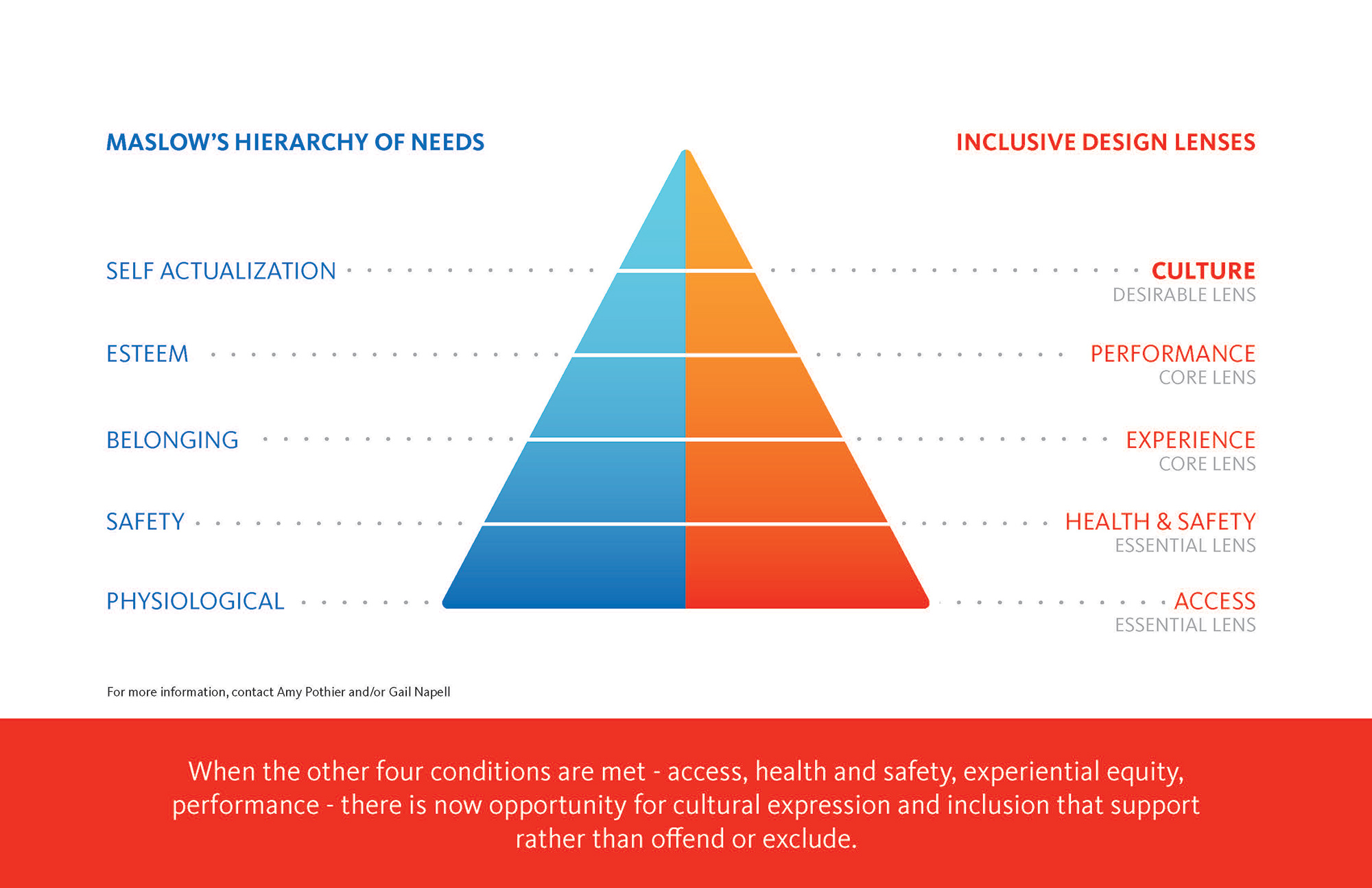

The idea of standardizing design elements and amenities that benefit people later in life is so sensible, yet seldom understood or addressed. I have found common purpose with my colleague Gail Napell, global Design Resilience Leader and co-founder of Gensler’s Inclusive Design Network. The Inclusive Design team has recently spearheaded the creation of Gensler’s Guide to Inclusive Design. Defined therein as "design for all people; [inclusive design] incorporates design solutions that meet needs related to gender identity, race, ability, age, neurodiversity, socioeconomic status, and culture, and is considerate of the ways in which these needs may intersect."

To ensure smooth elevator access, automated doors, stair alternatives such as ramps and gradual inclines, and safety handles is something that many older individuals need. But all human beings, regardless of whether they have mobility challenges or injuries, also benefit from these design decisions. A building manager will never get a complaint that an elevator is too accessible, or that a ramp is too accommodating for tenants moving into a new unit or hauling groceries. Features like this are common sense.

Such design considerations are often reduced to checkbox items to meet accessibility code requirements, a reality Gail is quick to critique: "Meeting minimum codes and legislative standards is not enough. Codes are reactive and not forward thinking in terms of what individuals truly need integrated in the built environment. We shouldn’t accept the minimum"

3. Scientific and medical best practices should inform design decisions that affect older adults.

There are few better examples of how to design for a wide range of human needs than the OhioHealth Neuroscience Wellness Center. Located in Columbus, the interdisciplinary center offers clinical, exercise, education, and emotional support programs to people living with neurologic conditions and their caregivers. It helps its members build strength, health, and community through comprehensive mind-body-spirit care. In 2023, the American Institute of Architects honored OhioHealth Neuroscience Wellness Center as a Winner of its prestigious 2023 Healthcare Design Awards, which recognize “cutting-edge designs that help solve aesthetic, civic, urban, and social problems while also being functional and sustainable.”

Organized around an outdoor courtyard and community hearth space, the center includes wellness and exercise studios with overhead harnessing for extra balance; a quiet studio for mind-body classes with a deck that extends for outdoor programming; multipurpose fitness rooms; an indoor walking track; a café; and the OhioHealth John J. Gerlach Center, which includes cognitive neurology and geriatric assessment clinics.

Frictionless design considerations are integrated throughout the space, including abundant and controlled natural light and views, transition spaces between indoors and outdoors, subtle material transitions, and clear and intuitive wayfinding, all in support of creating a neurowellness-centered, tranquil environment. One AIA juror noted that the project “clearly addresses the needs of the clientele it’s serving. It also captures the idea of beauty so well,” prioritizing the surrounding landscape and access to daylight.

4. Intergenerational mixed-use developments should redefine our idea of community.

As The New York Times has recently pointed out, “intergenerational housing — development that goes out of its way to mix older and younger people — is increasingly regarded as healthier, physically and psychologically.” To create flexible residential units that one could reconfigure to connect an adjacent unit for a live-in caretaker is obviously a wonderful thing for someone who wishes to stay in their home later in life. But it is also a wonderful thing for a couple starting a family, or a group of friends looking to share an apartment after college. We miss such opportunities at our peril.

College campuses are likely to stretch the new intergenerational paradigm even further. Among the exciting new models that are emerging are university-based retirement communities (UBRCs), which merge several types of housing for older adults with access to the medical centers, transportation, fitness facilities, libraries, entertainment centers, and other amenities that energize campus life. Most of these communities allow residents to enroll in college courses, providing ample outlets for renewed individual purpose in addition to mentorship opportunities with younger students. With college enrollment among retirees reaching an all-time high, and with many college campuses struggling to meet in-person enrollment numbers among traditional students, these alternative development routes could prove fortuitous.

Gensler has been a consistent advocate on the issue, publishing a series of articles in 2017 that paved the way for the rollout of our BoomTown community model, a research project outlining how to create a community for all ages that fosters interaction across generations as they live and grow.

The BoomTown project emphasized a key finding, that most soon-to-be “retirees” want to work in other capacities when they retire, and they take pleasure in the same amenities as millennials do. The implications of the demographic shift are by no means limited to residential life: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as cited in a recent AARP study on ageism in the workforce, “The number of workers age 50-plus has increased by 80% over the past 20 years, more than four times faster than overall workforce growth.” Moreover, “Among those age 65-plus who are currently employed, over 40% intend to work for at least five more years.”

Hence the need not only for new residences, but an entire BoomTown. Humanity’s future, across all walks of life, will only become more intergenerational over time. All of which brings us back to those surprising statistics I mentioned at the top. Think about it: What do you want to do with your last 40 years? It’s time for all of us to take that question very seriously, and to design for long, active, purposeful, and connected lives.

For media inquiries, email .