For People to Stay, They Need Places to ‘Go’

Public restrooms are an essential yet often overlooked link in urban renewal, allowing people to pause, linger, and enjoy city life.

After years of pandemic-era disruption, America’s downtowns are stirring back to life. Office workers are returning, tourists are visiting, and new retail and residential projects are reshaping urban cores. Yet even with this visible resurgence, one key challenge remains: getting people not just to pass through downtowns, but to stay there.

According to Gensler’s City Pulse 2025, people are drawn to cities that meet essential needs: comfort, safety, accessibility, and they stay in places that foster emotional connection. But recent behavioral research reveals a troubling trend: compared to 1980, pedestrians today walk about 15% faster and spend half as much time in public spaces. In other words, downtown streets have become corridors of efficiency rather than places for discovery.

Encouraging people to pause, stop for coffee, or simply watch street life unfold is critical for civic vitality. Public restrooms are one of the most overlooked enablers of that experience. As Gensler’s own research affirms, “safe, dignified access to public restrooms is a human right — essential for participation in civic life.” If cities want people to spend time strolling their streets, they must also make the experience comfortable, which means providing convenient, clean places to ‘go.’

The United States lags far behind its global peers in public restroom infrastructure. On average, the U.S. has only eight public toilets per 100,000 people, compared to 15 in the U.K., 23 in France, 37 in Australia, and 56 in Iceland. Even our most visited cities fall short: New York City averages just four public restrooms per 100,000 residents.

For decades, Americans relied on the “borrowed” restroom: a patchwork system of restrooms at coffee shops, libraries, or fast-food chains. This fragile ecosystem collapsed during the COVID-19 pandemic, making visible what urban advocates had long known: the absence of public toilets is a quiet urban crisis. Without restroom access, people are left with undignified or unsafe choices, contributing to public health and sanitation issues and limiting their participation in public life.

From Myths to Opportunities

Public restrooms in the U.S. have long been weighed down by assumptions that they are misused, expensive, or unpleasant, but the act of taking them away has been nothing but punitive to the public. At Gensler, we know that design can make all the difference in how these amenities are perceived and integrated into civic infrastructure.

Take the misconception that public restrooms attract unwanted behavior. The opposite is often true: well-lit, transparent, and actively maintained spaces invite safety. When design brings visibility and dignity, the facilities themselves become guardians of public order, not threats to it.

Cost, another frequent objection, overlooks the proven efficiency of modular solutions like the Portland Loo. These compact, durable structures demonstrate that low-maintenance doesn’t have to mean under-designed. They’re intentionally simple, built with long-term sustainability in mind, and are easily replicated across districts without straining budgets.

When cities make it easier for people to linger comfortably outdoors rather than rush home, the added dwell time drives more foot traffic and retail activity, turning public restrooms from cost centers into economic drivers that keep people and spending in the public realm.

Ventilation, durable materials, natural light, and visibility all encourage respect and responsible use. Cities that treat restrooms as civic architecture see higher usage and less vandalism. Take Japan’s exquisitely designed public restrooms, which became national icons.

Each of these misconceptions is an opportunity to design smarter systems and make public spaces more equitable.

Planning the Framework for Access

According to the American Restroom Association, people should be within a 10-minute walk or roughly a quarter to half a mile of a public restroom in major pedestrian areas. This means locating facilities at natural nodes of activity such as transit hubs, parks, plazas, and waterfronts, where foot traffic is highest.

Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 reinforces this priority. Public restroom availability ranks among the strongest amenities that predict a great experience for both downtown residents and employees.

Alongside strategic placement, the density and scale of facilities should respond to local context. A small neighborhood park might need only a single-stall unit, while a large regional park or downtown square could require a multi-stall pavilion or several modular units to accommodate peak crowds. Cities can use foot traffic data, event schedules, and user surveys to determine where facilities will have the greatest impact.

Visibility is equally important, since clear wayfinding and signage with universal symbols, multiple languages, and digital mapping help residents and visitors locate nearby restrooms with ease. New York City’s new Google Maps public restroom layer shows how improving information access can be as powerful as adding new infrastructure.

Finally, future-proofing the structures is essential. Structures should incorporate climate resilience and emergency preparedness, including off-grid power generation that can double as a power charging station and a utility node for water and sanitation utilities. Strategic placement that allows space for expansion, such as temporary tents during crises, is also critical.

Ultimately, a comprehensive restroom network should read like a transit map: accessible, legible, equitable, and resilient.

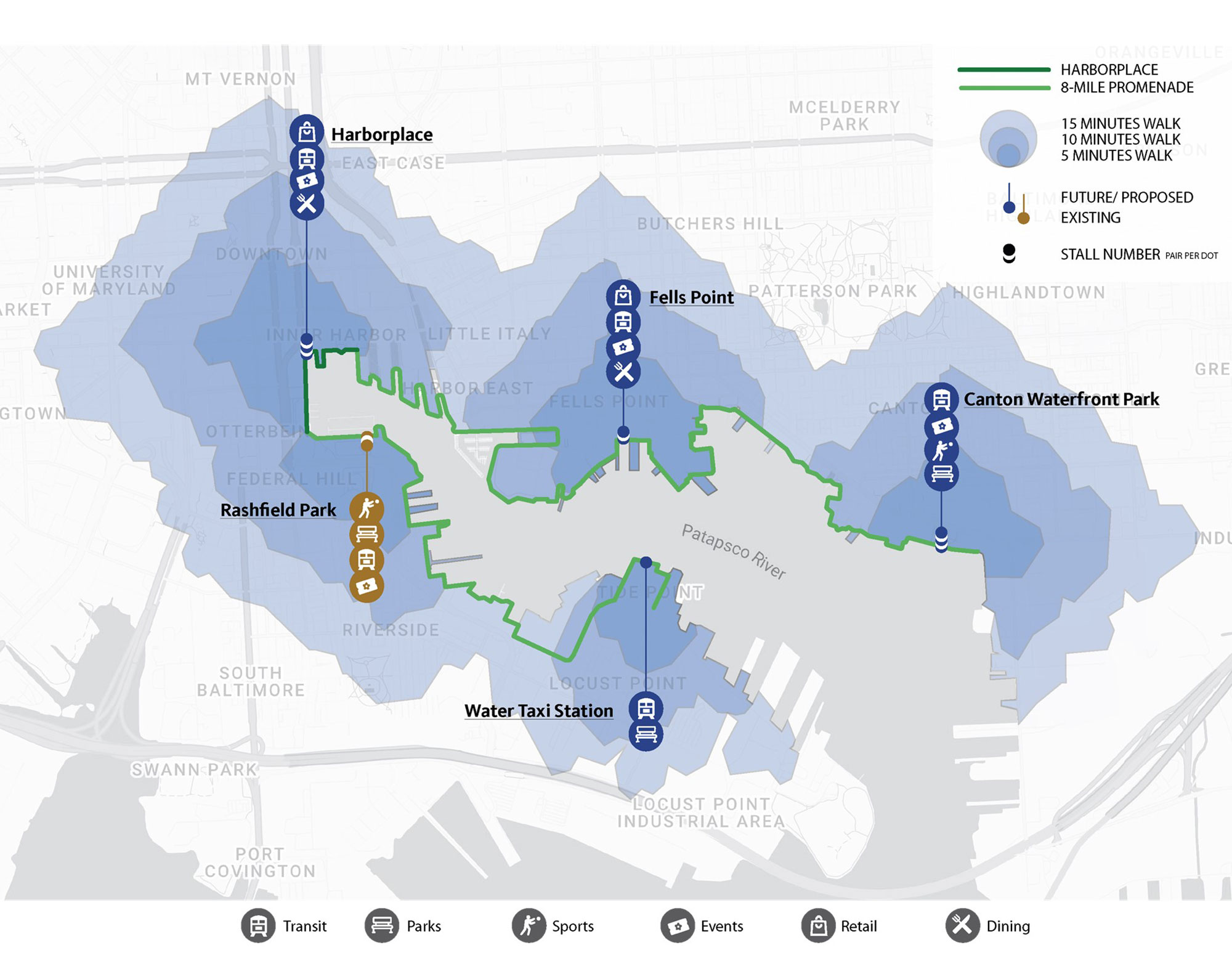

Baltimore’s Downtown RISE plan offers a timely example of how cities can invest in public restroom access. The ongoing improvement plan for the city’s eight-mile-long waterfront promenade incorporates public restrooms at key destinations such as the proposed Harborplace redevelopment and Rash Field Park Pavilion, strategically connecting major attractions and transit stops.

Mapping these amenities through walkshed analysis to identify five, 10, and 15-minute walking distances can help the city visualize coverage gaps and plan future facilities where they are most needed.

Designing Dignity Into the Urban Core

Portland’s durable and replicable Portland Loo, San Francisco’s staffed Pit Stop Program, the smart “Throne” units being tested in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., and New York City’s growing network of mapped park restrooms are all examples that show that thoughtful design and steady investment can restore comfort, dignity, and trust in the public realm.

A well-designed and free facility can anchor a park, support a waterfront, or enhance a downtown retail corridor. For developers, including a publicly accessible restroom in or near a project can enhance foot traffic and social value, and even help projects qualify for development incentives. For civic leaders and urban planners, restrooms should be a key focus.

Public restrooms might not be glamorous, but they represent a critical threshold of inclusion in public life. They allow people to participate in festivals, gatherings, and everyday errands with convenience and comfort. As we reimagine our downtowns to be more equitable and resilient, we must include these humble yet powerful spaces in the plan. When people know there’s a clean, safe place to go, they’ll stay a little longer.

For media inquiries, email .