Survivalist Architecture: The Age of Adapt & Reuse

The real estate market is rapidly evolving towards a net-zero carbon future, and architecture is following suit. With organisations everywhere increasingly aware of climate change, a sustainable surge is driving demand for game-changing innovations in construction processes and the materials industry. In the face of limited resources, evolving space needs, and aging buildings, we will achieve our goals by leaning into adaptive reuse strategies to reimagine existing spaces.

Resilient, sustainable design and adaptive reuse are no longer optional; they are essential to reducing emissions, conserving resources, and creating buildings that can endure the challenges of a changing climate. This shift signals a redefinition of architecture, moving beyond pure aesthetics to embrace solutions that prioritise environmental and social responsibility. The ideologies that shaped architectural design over the last century are losing relevance, giving way to new values that redefine the design process and the buildings that emerge from it.

We spoke with Harry Cliffe-Roberts and Valeria Segovia, principals at Gensler’s London office specialising in adaptive reuse, as they share insights on architecture’s evolving role in today’s world.

What do you see as the next big evolution in architecture?

Harry Cliffe-Roberts: We’re on the brink of another transformative moment, driven by the urgent need to address environmental crises. This evolution challenges established norms and pushes us to rethink how we design with the planet in mind. It’s a shift that might be uncomfortable for some, but it’s necessary and holds the potential to reshape our roles and the impact of our work. Architecture is becoming less about individual expression and more about collective responsibility.

Valeria Segovia: We’re embracing a philosophy where “the new is old, and the old is new.” Instead of starting from scratch, we’re finding new purposes for existing materials — repurposing steel, refurbishing ceiling tiles, and transforming brick façades. This approach celebrates creativity in working with what we have and reflects a broader commitment to sustainability. It’s about appreciating the past while innovatively crafting a future that’s mindful of our environmental footprint.

The Acre in London is a great example of this mindset in action. We retained 80% of the original Brutalist structure and reimagined it as a vibrant, community-focused workplace. By preserving its concrete structure while opening it up to the city, we were able to reduce embodied carbon, celebrate the character of the original design, and create something entirely new and future-facing.

How do you see the role of the architect evolving in the future?

Harry: The era of starting projects on a blank slate is fading. Buildings are rarely singular acts of authorship by one architect anymore. We’re moving towards sustainable, purpose-driven design where there’s often a clear ‘right’ answer beyond aesthetics. Our challenge is to work within the existing fabric, evolving and adapting structures to find new relevance for the future rather than erasing their history. Future architectural leaders will balance creativity with carbon-conscious design, ensuring that every choice reflects a commitment to sustainability.

Valeria: And that means we need to rethink our traditional processes. Linear design stages, like the RIBA framework, are becoming outdated. The design process is more fluid now, requiring early integration of construction considerations. Architects must upskill and adapt, incorporating sustainable thinking from the outset. This holistic approach is essential for aligning our designs with the complex environmental challenges we face today.

How is the role of data influencing architectural design today?

Valeria: Data is crucial in validating our design decisions. We can no longer justify demolishing and rebuilding without fully understanding the context of existing structures. By studying a site’s history, its community, and its environmental impact through both quantitative and qualitative analysis, we can set clear, data-driven goals. This approach helps us make informed choices, leading to more responsible and impactful architectural practices.

Harry: Absolutely. It’s about looking at what’s already there and understanding the opportunities and challenges it presents. Every decision — from what elements to preserve to how we prioritise carbon intensity — needs to be guided by data. This mindset moves us beyond pure aesthetics and personal preference, aligning our work with broader sustainability goals. The architects who can effectively integrate data-driven insights with creative design will be the ones leading the next evolution in our field.

How would you define the current architectural movement?

Harry: Modernism helped us move beyond ornamentation with its ‘Form Follows Function’ philosophy, but today we’re pushing further into what we call ‘Survivalist Architecture’ — where ‘Form Follows Responsibility.’ It’s about ensuring every design decision is anchored in environmental impact and future responsibility. Our work is no longer just about individual expression; it’s about addressing collective challenges and making a lasting, positive impact.

Valeria: Our work is part of a continuum, a dialogue with the past, and a responsibility towards the future. Each project is a chance to honour what came before while pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. It’s about leaving a legacy of stewardship, creativity, and resilience, ensuring that architecture continues to evolve with purpose and integrity.

So, will there be no new buildings in the future?

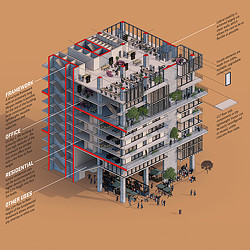

Harry: An adaptive reuse approach will certainly become a common starting point. Every site is different, and a consistent and objective viability process is crucial in understanding the suitable approaches for each asset. However, we believe that wholesale demolition and complete new build schemes will become harder to justify. That means we should start to think of each project as an opportunity to create a new product, with the variable being the degree of retention of existing fabric and material. We can expect a range of interventions, from comprehensive ‘refresh’ schemes that focus on wholesale retention, to new build and partly retained projects that fall at the ‘reenvision’ end of the spectrum.

Valeria: Regardless of scale, the richness in narrative that adaptive reuse projects can provide is what sets them apart. This narrative establishes a strong project purpose and can define a building’s identity.

The future of buildings depends on how we evaluate what good design truly means. We need to shift our perspective to value materials that don’t necessarily come straight from the earth to materials that have lived a past life, even if in a different form. Reused and recycled materials are inherently beautiful, and biomaterials — quite literally full of life — represent an exciting opportunity for innovation within the construction industry. Every layer of history in a building and its components adds depth to its story, creating projects rich in meaning and connection. In many ways, the “new” new build is made from old parts, reimagined for a future that embraces sustainability and creativity.

At 100 New Bridge Street in London, we embraced a circular economy strategy from the outset — not just as an environmental commitment, but as a business strategy. We treated the building as a “material bank,” identifying and repurposing thousands of square meters of ceiling tiles, granite cladding, stone ballast, and structural elements. Instead of sending these materials to landfill, we found ways to reincorporate them into the design, from ceiling rafts to terrace finishes.

It’s adaptive reuse on a deeply integrated level, and the recent sale of the building, which is a significant bellwether for the central London office market, proves that sustainability, beauty, and commercial value go hand in hand.

For media inquiries, email .