The Benefits of Converting Class C Office Into First Class Residential

Los Beneficios de Convertir Edificios de Oficina Clase B y C en Residencia

June 14, 2021 | By Steven Paynter, Duanne Render

14 de junio de 2021 | Steven Paynter, Duanne Render, y Lola Guevara

Going into the pandemic, the city of Calgary was already facing an existential crisis, with office vacancy rates rising to 24% due to plunging oil prices, according to an Avison Young market report. A year later, and the corporate office vacancy rate is hovering at around 32% — double that of Detroit’s when the city declared bankruptcy in 2014. Calgary now has 12 million square-feet of vacant office space on the market. So, what should be done with all that empty office space, and how can cities like Calgary tackle rising vacancy rates?

The shift to more modern, amenity-rich, and sustainable Class A office buildings was happening even before the pandemic. Aging office buildings are now sitting empty as tenants choose more modern buildings, and not just in Calgary. Initially, the choices for landlords in a market with a glut of office space were to renovate and retool buildings with refreshed amenity spaces. But now, in a post-pandemic and hybrid work economy, tenants’ priorities have changed, and many are demanding a unique office experience that cannot be replicated at home. And this cannot be accommodated in the aging Class C office stock.

Many Canadian cities went through a building boom in the late ‘60s and ‘70s and those buildings are now at end of life, requiring significant investment to bring them up to modern standards. From coast-to-coast, clients are facing a similar challenge: in order to future-proof their older buildings, they’ll need to make their buildings more energy efficient, more resilient, and ultimately more vibrant to attract and retain tenants and talent. That means older Class B and C buildings might not be worth the investment to bring up to current needs.

In today’s evolving office market, how can developers and building owners assess whether to upgrade an older, poorly performing building as office space or convert it to other uses, in order to get a better return on their investments?

Gensler’s research to help asset holders evaluate conversion potential of underperforming buildings got the attention of Calgary’s real estate working group and we partnered to develop a tool and cost model, which led to the city approving an initial investment of $200 million for a downtown revitalization plan, with $45 million for incentives towards the conversion of existing office space to residential, redevelopment, or adaptive reuse.

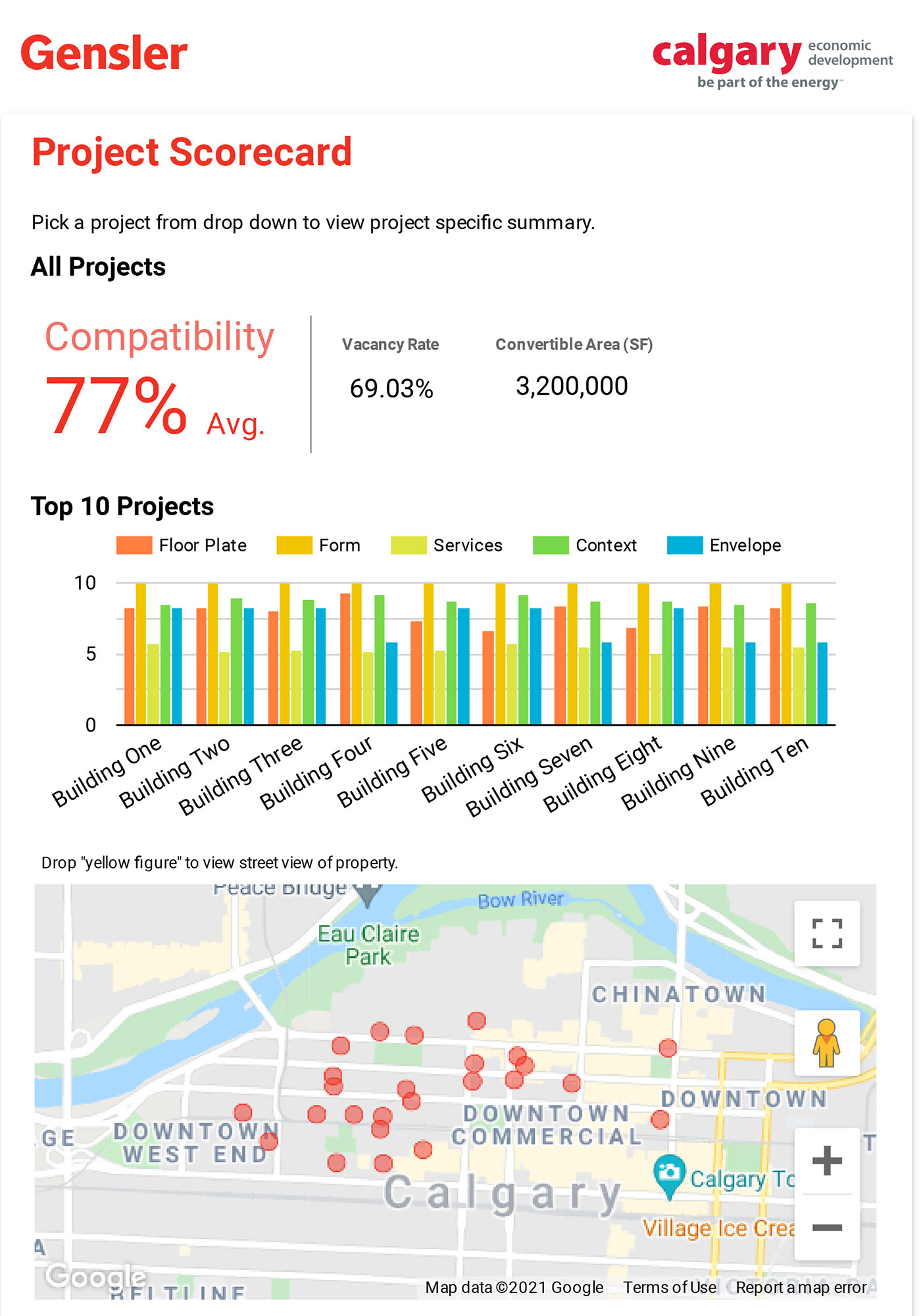

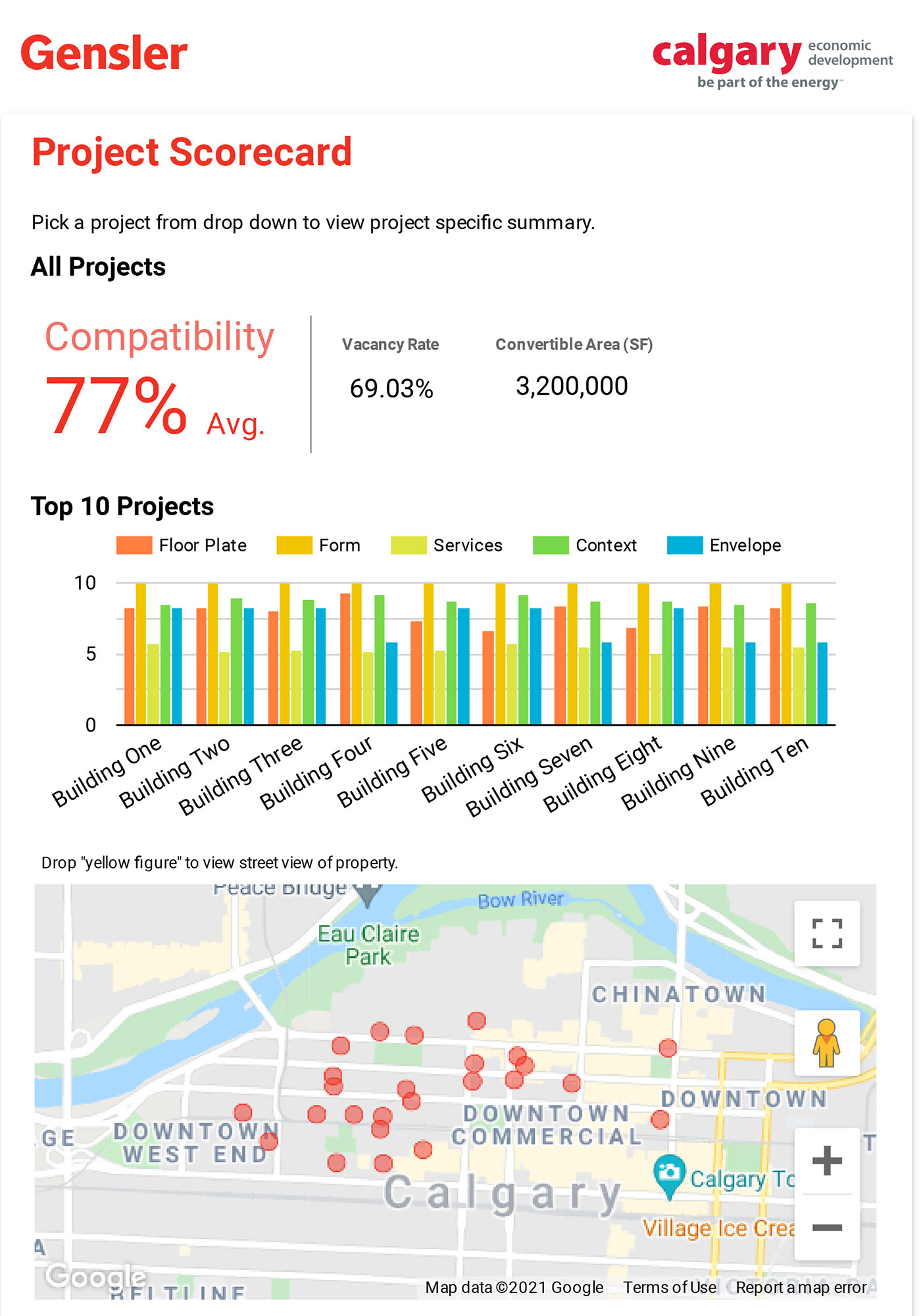

The Calgary Economic Development commissioned Gensler for a study, and we used our universal scorecard to understand which underperforming buildings could efficiently be converted from office to residential. The scorecard, which can be used anywhere in the world with minor adjustments, assesses all the factors that make for a good residential building — how deep the floor plate is, the ceiling heights, how many elevators, neighborhood context, access to transit, and parking.

In studying 28 buildings in Calgary, totaling 3.2 million square feet, we discovered that about 30% (10-12) were viable candidates for conversion. If all 12 were converted, that would create space for approximately 4,000 people to start calling downtown home, with an additional 2,000 units on the market.

In Calgary, these buildings are clustered in the west of the city. We believe this is a positive factor because if a number of buildings convert from office to residential simultaneously, it creates a positive downstream effect on the neighborhood. Services spring up to support residents, and it suddenly makes sense for city councils to invest in parks, libraries, and improved transit. If the buildings were geographically spread out, there wouldn’t be the same level of impact over a relatively short period of time.

Bad office makes for good residentialSo what buildings are the best candidates for office-to-residential conversion? Perhaps counterintuitively, we found that the “worse” the office building (typically Class C buildings), the better candidate they are for conversion to residential. Class C buildings typically have 11 foot floor-to-floor heights — 8 foot or 7 foot 6 inches clear once you factor in all the ducts and cabling that runs through. In office buildings, that’s now considered almost oppressively low, making for a gloomy, cramped feeling. By stripping out the ducts and ceiling tiles, we can create ceilings for residential that are 10 foot high, which is more generous than many new-build residential towers, allowing for lots of light and spacious-feeling apartments.

Vacancy to vibrancyBeyond the challenge of adapting older buildings lies the risk inherent in such a move. In order to incentivize asset holders and build consensus within and between the public and private sectors, we conducted research into other cities that had made similar moves, and we examined what the city councils in these cities had done to stimulate change.

We reviewed tax incentives, credits, and other economic levers that cities had at their disposal. We also wanted to find other places that had successfully undertaken a transformation of this scale. The two stand-out success stories were Detroit and Kansas City.

In Detroit, the Shinola Hotel has been a significant catalyst for change. Transforming four buildings into a unified hospitality anchor in the city’s historic Woodward shopping district, the newly renovated hotel is credited with helping to revive the neighborhood; shops, cafes and restaurants have now sprung up around the hotel.

Similarly, Kansas City has at least two dozen underperforming downtown buildings that have already been saved from ignominy through adaptive reuse, redevelopment, and repositioning. Another dozen are reliably in progress to become housing or hotels, with six to 10 more on the horizon.

Both Detroit and Kansas City have successfully reinvigorated their downtowns and decreased vacancy rates by focusing redevelopments in a few concentrated areas. By offering a more diverse mix of residential, commercial, and entertainment, cities can revitalize downtowns and allow central business districts to thrive.

Adaptive reuse also makes sense when viewed through a sustainability lens. Construction contributes 11% to global carbon emissions, according to Architecture 2030, and adaptive reuse can cut that by up to 80%. Given this outsized impact, reusing our buildings impacts the triple bottom line — people, planet, and profit.

As stated in Gensler’s Climate Action Through Design 2021 report, by renovating existing buildings and repurposing spaces and materials, developers can decrease the amount of carbon associated with new materials, and they can reduce the amount of debris and waste going into landfills. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, deconstruction rather than demolition of a building can save 90% of a building’s materials.

Adaptive reuse is also much more cost-effective than building new. Demolition and new building costs can be side-stepped and, as is now the case in Calgary, developers can frequently access municipal incentives.

Today, Calgary faces tough challenges — too many empty office towers, an eroding tax base, and not enough people living and working downtown. For many Calgarians, the adaptive reuse revolution can’t happen soon enough.

For media inquiries, email .

Entrando en la pandemia, ya la ciudad de Calgary se enfrentaba a una crisis existencial. Las tasas de desocupación de oficinas ascendían a un 24% debido a la caída de los precios del petróleo (según un informe de mercado de Avison Young). Un año después, la tasa de desocupación de oficinas corporativas subió al 32%, el doble que la de Detroit cuando la ciudad se declaró en quiebra en el 2014. En ese momento, Calgary tenía en el mercado 1.1 millones de metros cuadrados de oficinas vacías. Entonces nos hicimos la pregunta, ¿qué se debe hacer con todo ese espacio de oficinas vacío y cómo pueden ciudades como Calgary hacer frente a las crecientes tasas de desocupación?

El cambio a edificios de oficinas de clase A más modernos, sostenibles y con más oferta de amenidades se estaba empezando a ver incluso antes de la pandemia. Los edificios de oficinas más antiguos están ahora vacíos porque los inquilinos optaron por edificios más modernos, y no sólo en Calgary. Al principio, en mercados con exceso de oficinas, los propietarios optaban por renovar y reequipar los edificios con nuevos espacios de amenidades. Pero ahora, en una economía postpandemia y de trabajo híbrido, las prioridades de los inquilinos han cambiado y muchos demandan una experiencia de oficina única que no se pueda replicar en casa. Esto es casi imposible de lograr en edificios de oficinas de Clase C.

En el caso de Canadá, muchas ciudades experimentaron un auge constructivo en las décadas de 1960 y 1970. Estos edificios están llegando al final de su vida útil, requiriendo una inversión significativa para modernizarse. A través del mundo, muchos propietarios y desarrolladores se enfrentan a un reto similar: para que sus edificios más antiguos estén preparados para el futuro, tendrán que hacerlos más eficientes desde el punto de vista energético, más sostenibles y además más dinámicos para atraer y retener inquilinos y talento. Esto significa que los edificios antiguos de Clase B y C podrían no valer la inversión necesaria para satisfacer las necesidades actuales.

En un mercado tan cambiante como el de oficinas, ¿cómo pueden los desarrolladores y propietarios de edificios evaluar si deben actualizar un edificio antiguo con bajo rendimiento como espacio de oficinas o convertirlo en otros usos para obtener un mejor retorno de su inversión?

La investigación de Gensler para ayudar a propietarios de activos a evaluar el potencial de conversión de edificios con bajo rendimiento llamó la atención de un grupo de trabajo de bienes raíces en Calgary. Nos asociamos con ellos para desarrollar una herramienta y un modelo de costos, lo que llevó a la ciudad a aprobar una inversión inicial de 200 millones de dólares para un plan de revitalización del centro de la ciudad. 45 millones de dólares serían destinados a la reconversión de oficinas existente a residencial, reurbanización y/o reutilización adaptativa de inmuebles existentes.

La Comisión de Desarrollo Económico de Calgary contrató a Gensler para realizar un estudio bajo el cual utilizamos nuestra herramienta de evaluación universal para comprender qué edificios con bajo rendimiento podrían convertirse eficientemente de oficinas a residencias. La herramienta, la cual con ajustes menores, puede ser utilizada en cualquier lugar del mundo, evalúa todos los factores que hacen que un edificio sea adecuado para uso residencial, como la profundidad de la planta, la altura del piso a cielo, la cantidad de elevadores, el vecindario, el acceso a transporte y el estacionamiento.

Al estudiar 28 edificios en Calgary, con un total de 300,000 metros cuadrados, descubrimos que aproximadamente el 30% (10-12) eran candidatos viables para la conversión. Si todos los 12 se transformaran, esto significaría que este centro de ciudad podría ser el hogar de más de 4,000 personas sumando 2,000 unidades residenciales en el mercado.

En Calgary, estos edificios están ubicados en una misma zona el oeste de la ciudad. Estas agrupaciones generan un efecto dominó positivo ya que, si varios edificios se convierten en residencias simultáneamente, se crea un efecto dominó en el vecindario. Surgen servicios para apoyar a los residentes y de repente tiene sentido que los gobiernos locales inviertan en parques, bibliotecas y en mejoras en el transporte público. Si los edificios estuvieran dispersos geográficamente, no se produciría el mismo nivel de impacto en un período de tiempo relativamente corto.

Mal desempeño en oficinas resulta en gran potencial para residencias.¿Cuáles edificios son los mejores candidatos para la conversión de oficinas a residenciales? Aunque resulte contraintuitivo, descubrimos que cuanto "peor" es el edificio de oficinas (generalmente edificios de Clase C), mejores candidatos son para la conversión a residenciales. Los edificios de Clase C suelen tener una altura de piso a techo de 3.4 metros que se reduce a 2.4 metros libres una vez que se consideran los ductos y cables necesarios agregar. Para oficinas, esta altura es extremadamente baja y se genera una sensación de oscuridad y estrechez. Al eliminar ductos y cielorrasos en todas las áreas comunes y dormitorios podemos generar alturas de 3 metros que son más generosos que muchas torres residenciales que se construyen hoy en día. Esto permite una mejor iluminación y apartamentos con una agradable sensación de amplitud.

De estar vacío a estar lleno de vida.Además del desafío de adaptar a los edificios más antiguos, existe el riesgo inherente de realizar este tipo de transformación. Para incentivar a los propietarios de inmuebles y crear consenso entre los sectores público y privado, fue necesario estudiar otras ciudades que habían adoptado medidas similares e investigar qué medidas habían tomado los gobiernos locales de esas ciudades para estimular el cambio.

Analizamos incentivos fiscales, créditos y otras herramientas económicas que las ciudades tenían a disposición. También buscamos otros lugares que hubieran llevado a cabo con éxito transformaciones de esta escala. Los dos casos de éxito destacados fueron Detroit y Kansas City.

En Detroit, el Hotel Shinola ha sido un catalizador de cambio. En el distrito histórico y comercial de Woodward, se transformaron cuatro edificios en una sola ancla unificada de hotelería. Se le atribuye a este renovado hotel haber ayudado a revivir el vecindario. Hoy han surgido tiendas, cafés y restaurantes alrededor del hotel.

Similarmente, en Kansas City al menos dos docenas de edificios se han salvado de la desgracia por medio de la reutilización adaptiva, la reurbanización y el reposicionamiento. Otra docena de edificios ya está en proceso de convertirse en viviendas y hoteles, y se vislumbran en el horizonte entre seis y diez más.

Tanto Detroit como Kansas City han revitalizado con éxito sus centros urbanos y han logrado reducir las tasas de desocupación al enfocar las reurbanizaciones en ciertas áreas concentradas. Al ofrecer una mezcla más diversa que incluya residencias, comercio y entretenimiento, las ciudades pueden revitalizarse y convertirse en distritos prósperos.

La reutilización adaptativa también toma sentido desde la perspectiva de la sostenibilidad. Según Architecture 2030, la construcción contribuye con un 11% de las emisiones globales de carbono, y la reutilización adaptativa puede reducir esto hasta en un 80%. Debido a este enorme impacto, la reutilización de edificios tiene afectación triple en: las personas, el planeta y las ganancias.

Como se menciona en el informe "Climate Action Through Design 2021" de Gensler, al renovar edificios existentes y reutilizar espacios y materiales, los desarrolladores pueden reducir la cantidad de carbono asociado con materiales nuevos y disminuir la cantidad de desechos y residuos. Según la Agencia de Protección Ambiental de los Estados Unidos, la deconstrucción en lugar de la demolición de un edificio puede salvar hasta el 90% de los materiales.

La reutilización adaptativa también puede ser mucho más rentable que la construcción nueva. Se puede evitar el costo de la demolición, la construcción nueva y, como esta ocurriendo hoy en Calgary, los desarrolladores pueden acceder con frecuencia a incentivos gubernamentales.

Hoy Calgary, así como muchas otras ciudades, enfrentan desafíos complicados: un exceso de edificios de oficinas vacíos, poca recolección de impuestos y muy pocas personas viviendo y trabajando en el centro. Muchísimo habitantes de estas ciudades, esperan con ansias los efectos de una revolución de reutilización y transformación.

Para consultas de los medios de comunicación, envíe un correo electrónico a .

Traducido por Lola Guevara, líder regional de edificios de oficinas y reposicionamiento, América Latina.