Birmingham Living: The Next Chapter

Gensler’s Residential leaders discuss how new housing, neighbourhoods, and communities are reshaping the city’s identity.

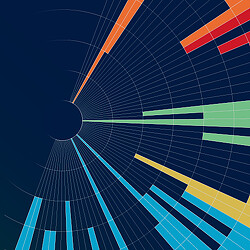

Birmingham is currently experiencing an exciting transformation, with new neighbourhoods and communities reshaping the city’s identity. As Gensler’s 2025 City Pulse Survey revealed, Birmingham ranks second among the top five international cities attracting new residents, with 22% of people moving into the city — a clear signal of the growing demand and opportunity within its residential market.

Building on this data and ideas shared by Gensler Birmingham Managing Director Madeleine Hilton in Birmingham’s Renaissance: The City of 100 Quarters, Gensler Europe Residential Leader John Badman, and Studio Director Jamie Rodgers, explore how housing is at the heart of this change, from creating vibrant mixed-use destinations to meeting the evolving needs of those who call Birmingham home.

John Badman: From what I’m seeing, the market feels alive, but uneven. Demand for new homes is strong across the board — from student living through to Build to Rent (BTR), co-living, affordable housing, and for-sale apartments. What’s shifting is expectation: whether renting or buying, people want service, amenity, and community as standard. City centre ownership is no longer just about buying a flat; it’s about having access to shared workspaces, gyms, gardens, and social areas that make urban living viable in the long term. The challenge is that too many schemes still feel like standalone objects. The opportunity is in mixed-use neighbourhoods where housing, across all tenures, is the anchor, and where every floor and every square foot contributes to both daily life and financial return.

One of the most promising solutions is the conversion of outdated, empty office buildings into new residential developments. At Gensler, we’ve developed a building analysis tool that can quickly review an office’s compatibility for multifamily conversion, reducing viability testing from weeks to minutes. This kind of innovation has unlocked developer interest in projects that might otherwise have been dismissed.

Now, looking at Birmingham specifically, how would you describe the current state of the city’s housing market, and where do you see the biggest opportunities for residential development?

Jamie Rodgers: You’ve mentioned a lot of what I’m seeing. In Birmingham, prices are up 1.2% in the owner-occupied market, and the rental market is growing faster, by about 6.2%. That’s partly driven by the cost-of-living crisis, but also by younger people who prefer flexibility over committing to a mortgage. Added to that, migration from London and Manchester is pushing things, both in demand and in what people expect from housing. You can see the skyline changing as a result of new investment tied to High-Speed 2 (HS2), Britain’s new high-speed railway. The real opportunity now lies in embedding residential in the city centre, which unlocks footfall, nightlife, and mixed-use vitality that Birmingham hasn’t yet fully achieved.

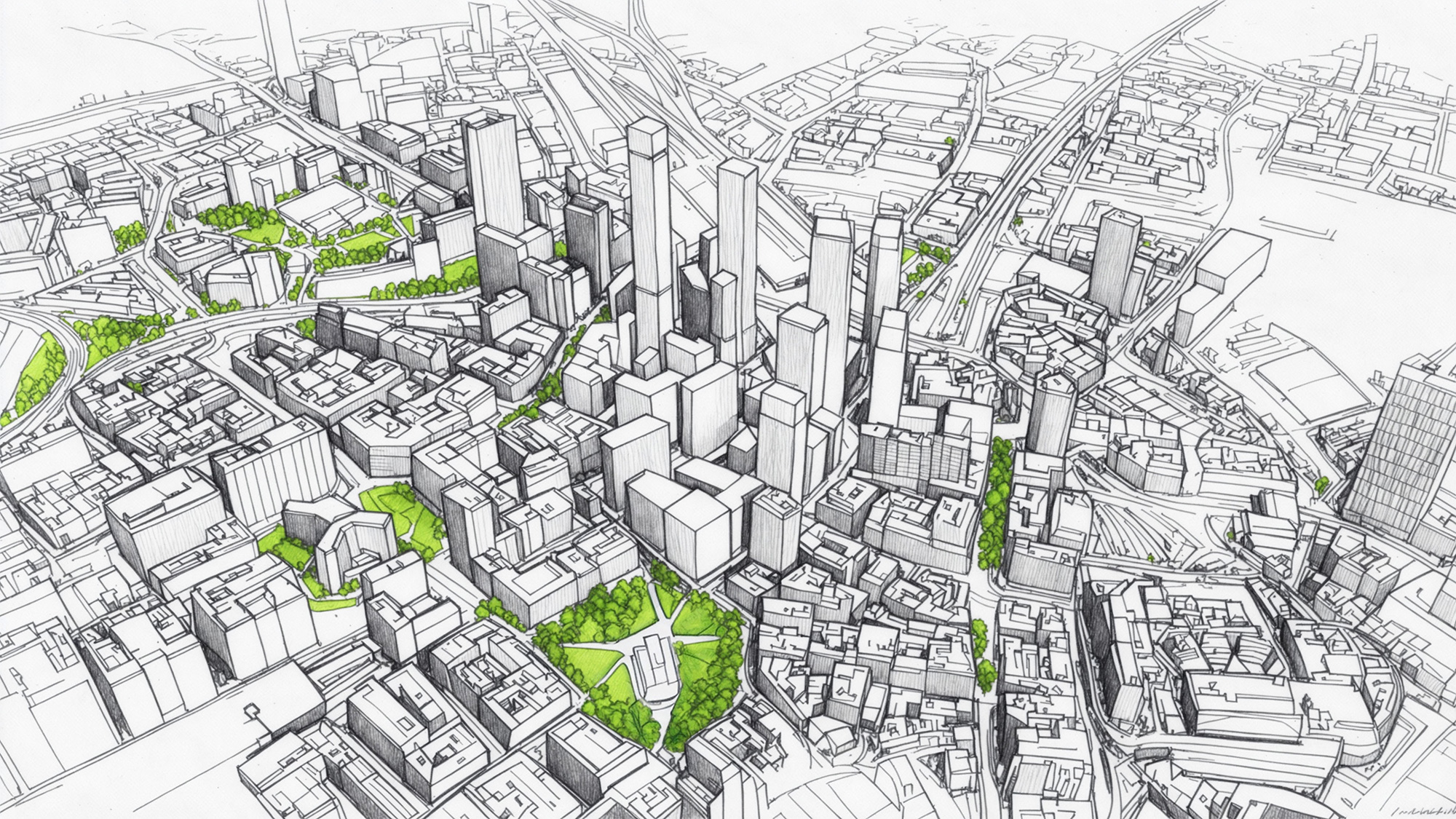

John: Looking ahead, the ‘100 Quarters’ concept opens many doors. I see Park Birmingham, especially near Curzon Street with HS2, as a huge opportunity, and the question is about the impact of that arrival and the sense of ambition that Birmingham offers. The ambition has to be an exciting, rich, active city centre — streets alive with culture, food, independent retail, and green public spaces. Residential is what will make that real: students bringing vibrancy, renters supporting ground-floor uses, owners providing long-term stability, and affordable homes ensuring inclusivity. To get it right, we need permeability in master plans, human-scale frontages, and neighbourhoods that feel authentically Birmingham. Done well, visitors will walk into a city that feels aspirational and lived-in, not just impressive on a drawing.

Which parts of Birmingham do you think are best placed for residential innovation already? And what design features are, or could be, making a difference?

Jamie: I completely agree — HS2 around Curzon Street sets the stage for that ambition, but it only works if it ties into the neighbourhoods around it. That’s why Digbeth is so critical. With projects like Smithfield and Connaught Square coming forward, you can already see the potential for the kind of vibrancy you described: cultural uses at street level, independent food and retail, and new residential layered on top. The challenge — and the opportunity — is making these quarters feel connected rather than like isolated pockets. If the master plans converge and the public realm stitches them together, then the food, beverage, and cultural offerings can really anchor residential communities. The local authority’s push for green space — from rooftop terraces with public access to green corridors — is helping, too. Those ingredients of greenery, community amenities, and active streets are exactly what will make Birmingham feel both aspirational and authentically lived in.

John: One thing I believe strongly is that reinvention is a strength in Birmingham. Reusing industrial or civic buildings brings texture and identity, but it also grounds new communities in the city’s story. That’s true whether we’re designing student housing, BTR, co-living, for-sale homes, or affordable housing. Each benefit from the depth that comes with heritage — materials, scale, and a sense of permanence. But there’s always the question:

How do you balance the old and the new so that new housing feels rooted and draws on local culture and heritage, rather than feeling like “imported design”? How are residential developers and planners in Birmingham doing with creating a true sense of belonging and community?

Jamie: Reinvention really is Birmingham’s superpower. The city’s heritage and culture, long known as the “city of a thousand trades,” give us an incredible foundation to build from. Storytelling through design makes that heritage tangible — whether it’s in material choices, architectural motifs, or cultural references that connect new buildings back to Birmingham’s identity. But as you said, belonging can’t just come from the bricks and mortar. It’s also about people. When residents are involved in shaping developments — through genuine consultation rather than a tick-box exercise — the result is places that feel inclusive and authentic.

And adaptive reuse ties both threads together. Repurposing underperforming office buildings not only preserves character and reduces embodied carbon but also addresses urgent housing needs. For Birmingham, it could be the catalyst that fuses heritage, sustainability, and community growth into a stronger, more resilient city.

John: With HS2, metro extensions, and new neighbourhoods emerging, there’s a major opportunity for residential design to support a more connected, walkable, sustainable city. I believe housing should open onto active streets, block sizes should be human-scale and easy to navigate, and green corridors should link transport nodes to neighbourhood centres. Also, density matters — enough to support schools, health, shops — but done at a scale people can relate to.

What are the requirements in Birmingham for this to work? Where are the constraints, and what design features can help?

Jamie: Families are central to Birmingham’s future, and while the local authority is rightly prioritising more three-bedroom homes, the supporting infrastructure must evolve in tandem — from quality childcare and accessible green spaces to dependable public transport. The vision is a walkable, people-first city. A key part of the solution lies in the quality of the public realm, and adaptive reuse: many office buildings, especially those underused post-COVID, can be transformed into residential spaces, helping meet housing demand while retaining architectural character. Looking ahead, master plans must be more ambitious and future-ready, embedding innovation, resilience, and net zero principles to ensure Birmingham meets the expectations of the next generation.

John: What I’m really excited about is how housing isn’t just filling gaps anymore — it’s leading the next chapter of Birmingham’s urban story. The diverse living sectors are maturing: BTR and co-living, student housing, affordable housing, and for-sale city living with amenities are all evolving. Mixed-use quarters have the potential to become real, lived-in places. The challenge is in delivery, with rising costs, planning uncertainty, and making sure communities are part of the change rather than having it imposed upon them.

What gives you optimism, and what would you like to see happening now, so we hit the potential rather than just the promise?

Jamie: I share that excitement. Housing really is becoming the driver of Birmingham’s transformation. What I take optimism from is the convergence you hinted at: if these different sectors and projects start talking to each other, they can create something far greater than the sum of their parts. That’s where the delivery challenge can actually become an opportunity.

Reimagining Birmingham’s historic districts is one example — it allows us to draw on heritage while still creating integrated, walkable neighbourhoods that respond to today’s needs. And the community has to be part of that, not an afterthought. At the same time, sustainability can’t just be a gesture; climate-resilient homes, green roofs, and passive design need to be embedded from the start. If we can align heritage, connectivity, and sustainability in this way, Birmingham really can set a benchmark for the future of urban living.

For media inquiries, email .