How a Challenging Site Fuelled a Bold New Workplace

A new building at The Goodsyard will transform an untapped site into a dynamic destination in London.

The role of the office is transforming faster than ever before. Office buildings need a unique personality to attract occupiers — and one way to achieve that is with a genuine connection to place.

The largest vacant site in London, Bishopsgate Goodsyard has been unused since 1964, located in a hugely challenging site spanning over the Shoreditch High Street railway station with a number of constraints. The new building at The Goodsyard, designed by Gensler in partnership with Ballymore and Hammerson, embraces these constraints as opportunities to craft an attractive, high-quality, and forward-thinking 550,000-square-foot workspace. By tackling the design challenges of the site in new ways, this building has developed a unique character that sets it apart, with several features that bring it to the cutting edge of workspace design.

The railway as a catalyst for innovation

At The Goodsyard, we set out to create a workplace that seamlessly integrates a diverse mix of occupiers, fosters innovation, and responds to its Shoreditch context. The design embraces a unique spatial strategy — one that wouldn’t have been possible without the challenge posed by the East London Line viaduct cutting through the site.

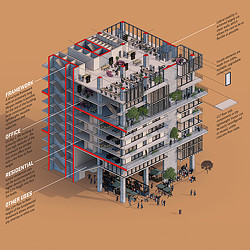

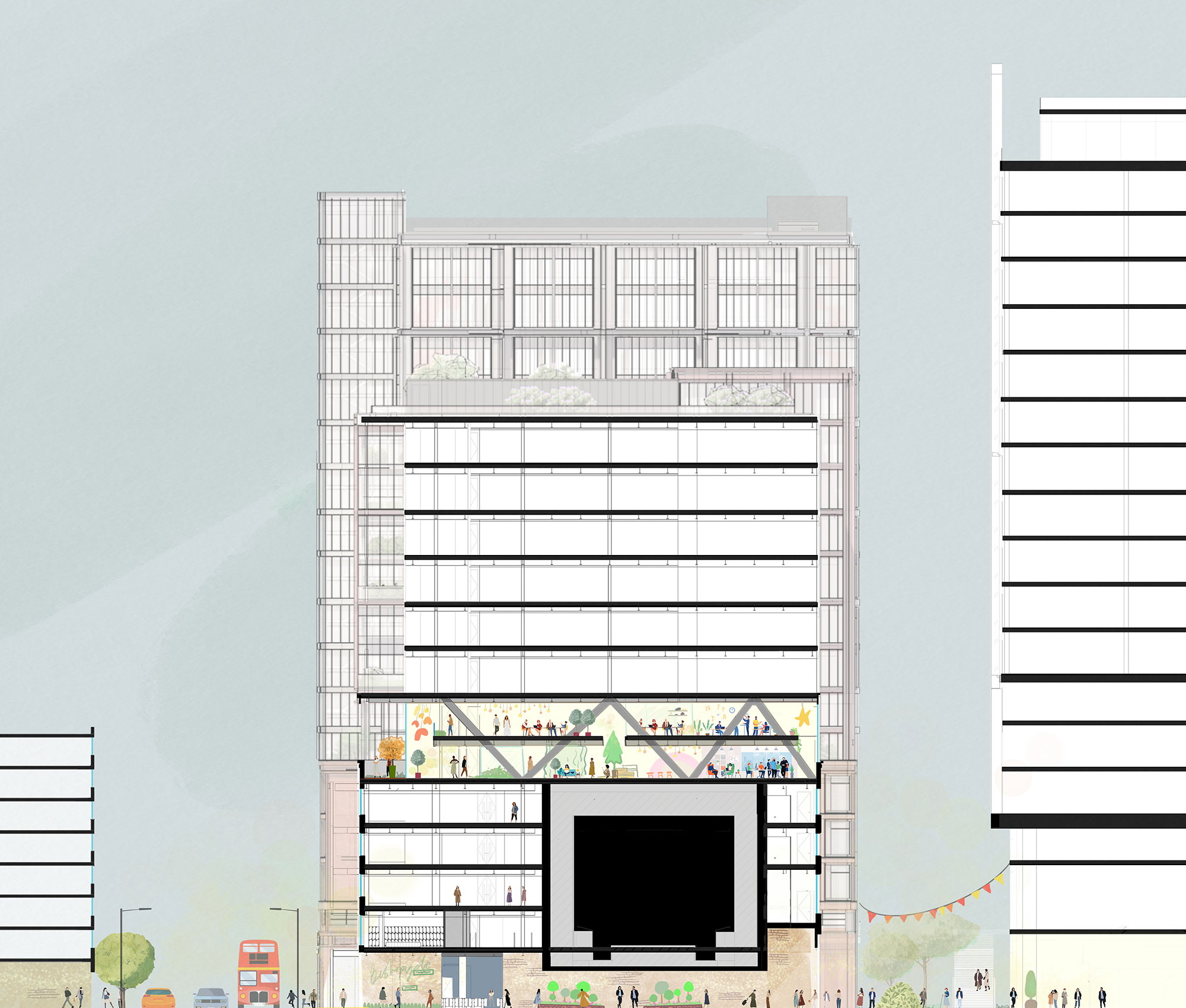

Rather than seeing the railway as a limitation, we leveraged it to create a dynamic, multi-layered workplace. The lower levels, shaped by shallow floorplates on either side of the viaduct, became ‘incubator’ spaces — boutique and affordable workspaces designed for startups and smaller businesses. These spaces offer increased flexibility, better access to daylight, and a stronger connection to Shoreditch’s creative energy. Meanwhile, the deeper floorplates on the upper levels cater to larger occupiers, creating a diverse and vibrant ecosystem within the building.

This divide between the ‘base’ of the building, with shallower floorplates and smaller tenants, and the ‘upper’ part of the building, with deeper floorplates suiting larger occupiers, informed the architecture’s overall expression. Whilst the deeper upper levels required maximum daylight, we used a more solid façade for the shallower lower levels. This had two benefits — first, it allowed us to maximise the insulation and thermal performance of the lower levels beyond what would be possible in most office buildings, and second, it allowed the building’s lower levels to tie into the historical elements of the surrounding historic Shoreditch buildings, integrating this office into its context.

A standout first-floor solution born from below-ground constraints

For this project, the design team embraced the opportunity to rethink how cycle facilities could be integrated into an office building — not as an afterthought, but as a standout feature. Instead of placing cycle storage in the basement, as is often the case, we elevated it — both literally and experientially — creating a premium first-floor facility with natural light, generous ceiling heights, and high-quality end-of-trip amenities.

This innovative approach emerged from the site’s below-ground constraints. Extensive structural offset zones for the railway viaduct and subterranean infrastructure, including a tube tunnel, left little room for a traditional basement. Whilst most office buildings of this scale incorporate full-site basements to house loading bays, plant, and cycle storage, here, we could only accommodate a compact space for water tanks.

Rather than seeing this as a limitation, we explored alternative solutions that might not typically be considered. By relocating cycle storage to the first floor and providing access via a prominent feature ramp from Bethnal Green Road, we transformed what is often a hidden space into a key selling point for the building.

Minimised embodied carbon amid structural challenges

At Gensler, we’re working to minimise embodied carbon across all our projects, guided by our Gensler Product Sustainability (GPS) Standards™ — a framework that sets sustainability performance criteria for the most used, high-impact materials in our architecture and interior projects. These standards, introduced in 2024, are a key step toward our 2030 carbon reduction goals, ensuring that every material selection is evaluated for sustainability alongside performance.

The structural requirements of this scheme presented a huge challenge in minimising embodied carbon, as carbon-intensive steel trusses were needed to enable the building’s large structural span over the station, and the site’s proximity to the railway prevented the use of mass timber. These constraints sharpened our focus on areas where we could meaningfully reduce embodied carbon. We designed an extremely efficient structural system with reduced spans and eliminated structural cantilevers to optimise material use.

Additionally, our minimal basement proved to be a key advantage, significantly reducing the amount of concrete in the substructure. The substantial carbon impact of basements is a critical learning we’ve applied to future projects, ensuring we minimise new basement construction wherever possible.

Designing a large building on a site as prominent as this will always be a fascinating design challenge, but at The Goodsyard, the challenging site led us to design a workspace that couldn’t be built anywhere else — and to design solutions we’re now bringing to other projects on less constrained sites.

Gensler’s design aligns with the wider masterplan, which envisions a new park in Shoreditch and the revitalisation of historic arches for retail use. Once complete, The Goodsyard site will create 11,000 new jobs and deliver up to 500 new homes, 1.4 million square feet of workspace, a new 2.6-acre public park, and restaurants, retail, and leisure spaces.

For media inquiries, email .