Rethinking Residential Unit Design: Lessons from Office-to-Residential Conversions

Strategic unit design creates better living experiences for residents and better performance outcomes for developers.

Standardized residential units are often the default in housing design because they streamline construction, cut costs, and speed up delivery. But this efficiency comes at a cost, limiting residents’ ability to choose homes that reflect their personal needs.

Gensler’s 2024 Residential Experience Survey of 1,300 New York Metro residents reveals that 53% of residents’ satisfaction with their housing experience stems from what happens inside their unit. While community and amenity spaces are important drivers of the overall experience, introducing variety in unit layouts expands market appeal and drives resident satisfaction.

Our analysis identified three primary resident types that transcend traditional demographics like income, gender, or household size:

- Social Seekers (35% of respondents) value hosting, gathering, and shared spaces, preferring large living areas, flexible lighting, and space for a formal dining table.

- Privacy Seekers (33% of respondents) use their homes as sanctuaries, prioritizing quiet, visual separation, and personal space.

- Comfort Seekers (32% of respondents) seek balance between work, rest, and self-care, valuing flexible layouts, larger bedrooms, and supportive amenities.

Residential satisfaction is not one-size-fits-all. However, most new or renovated housing still emphasizes uniformity. The solution may lie in an unexpected place: office-to-residential conversions.

Office-to-Residential Conversions: Turning Constraints Into Competitive Advantage

Office-to-residential projects face unique structural challenges, such as irregular floor plates, varied ceiling heights, and unconventional layouts. Forward-thinking developers leverage these irregularities to create unit diversity that purpose-built multifamily housing typically lacks. The result: a differentiated product that better aligns with residents’ lifestyles.

Pearl House in New York offers a compelling case study. Its 30 unique unit plans and central location have attracted a diverse mix of residents, achieving full occupancy by supporting multiple lifestyle types.

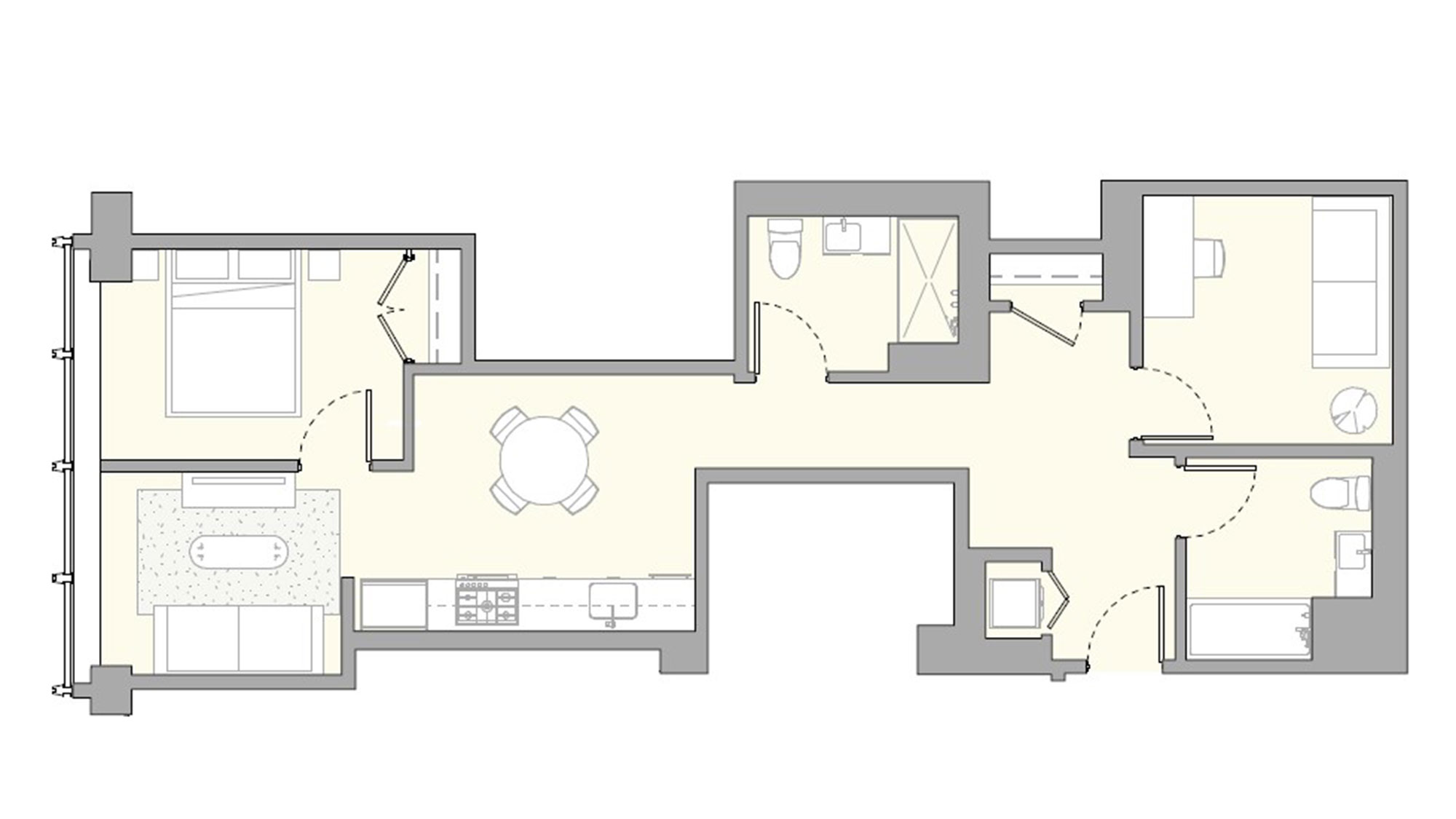

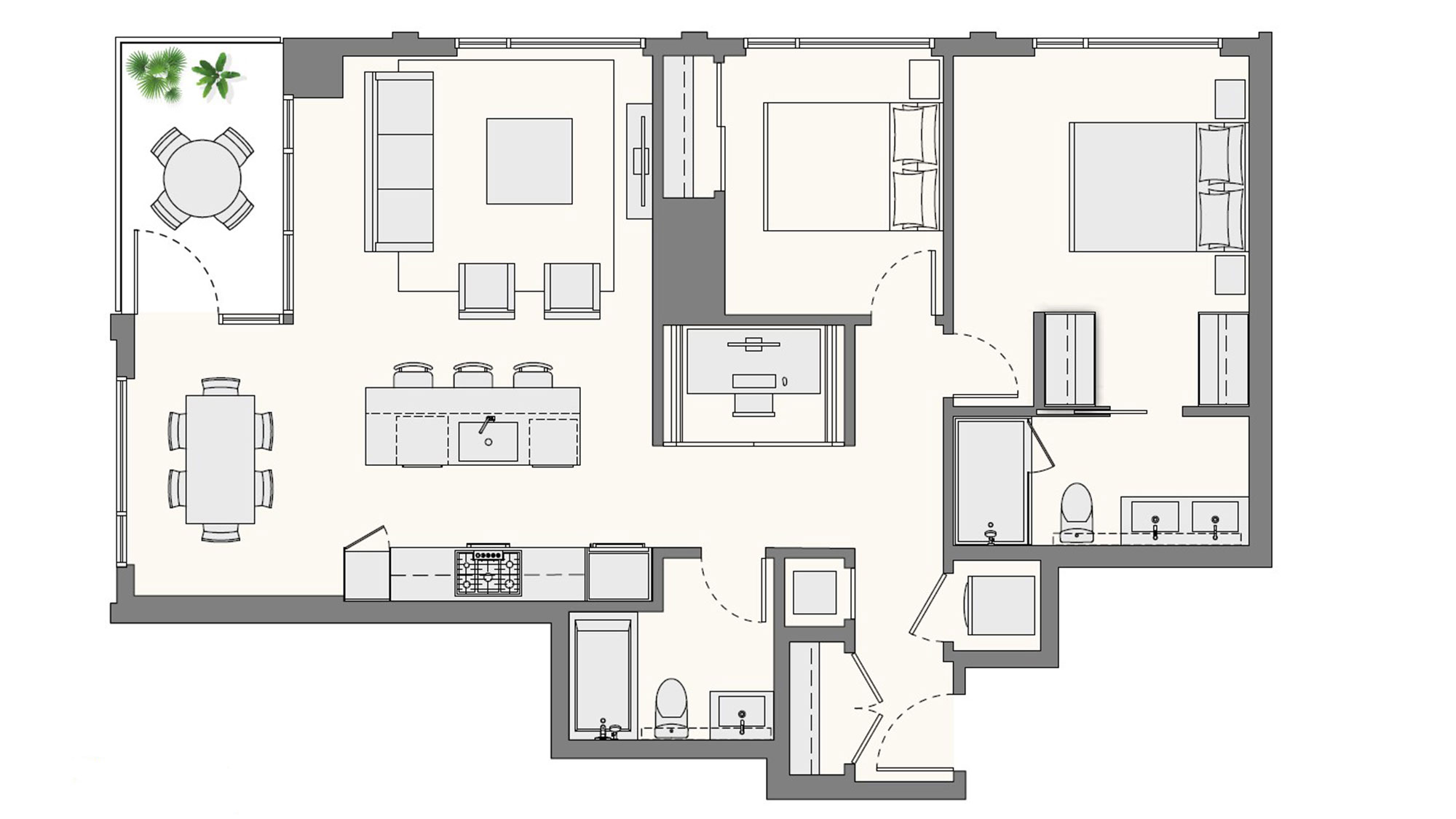

Take the tower’s Unit A, shown below. Arranged with a dedicated home office and an eat-in kitchen that opens directly onto the living room, this unit lends itself to the lifestyle of the comfort seeker — people who enjoy the comforts of home, and want to maintain separate spheres between living, working, and sleeping. This configuration appeals to hybrid workers and wellness-focused renters — growing segments that command rent premiums.

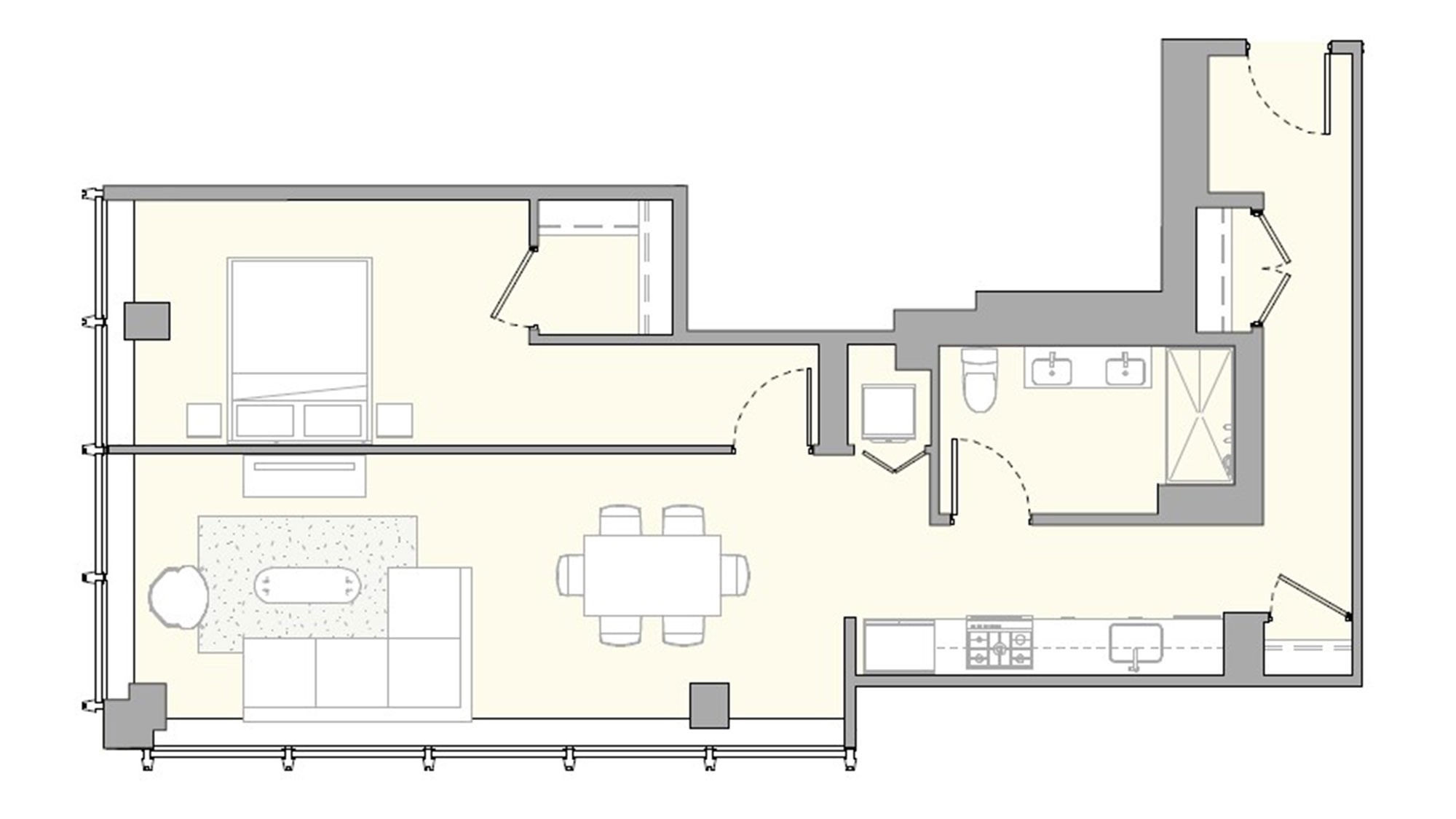

Pearl House’s Unit B takes a starkly different approach, catering to the privacy seeker. Privacy seekers value the extended foyer of this unit, which shields the living-dining area from the outside hallway. Residents can add a formal dining area between the separate kitchen and living room or use substantial wall space for personal art and objects.

The foyer creates physical distance between their living space and the outside world, prompting a sense of arrival in a place of refuge. The bedroom furthers this separation with its own arrival area and double closet. These strategies reinforce the home as a private sanctuary.

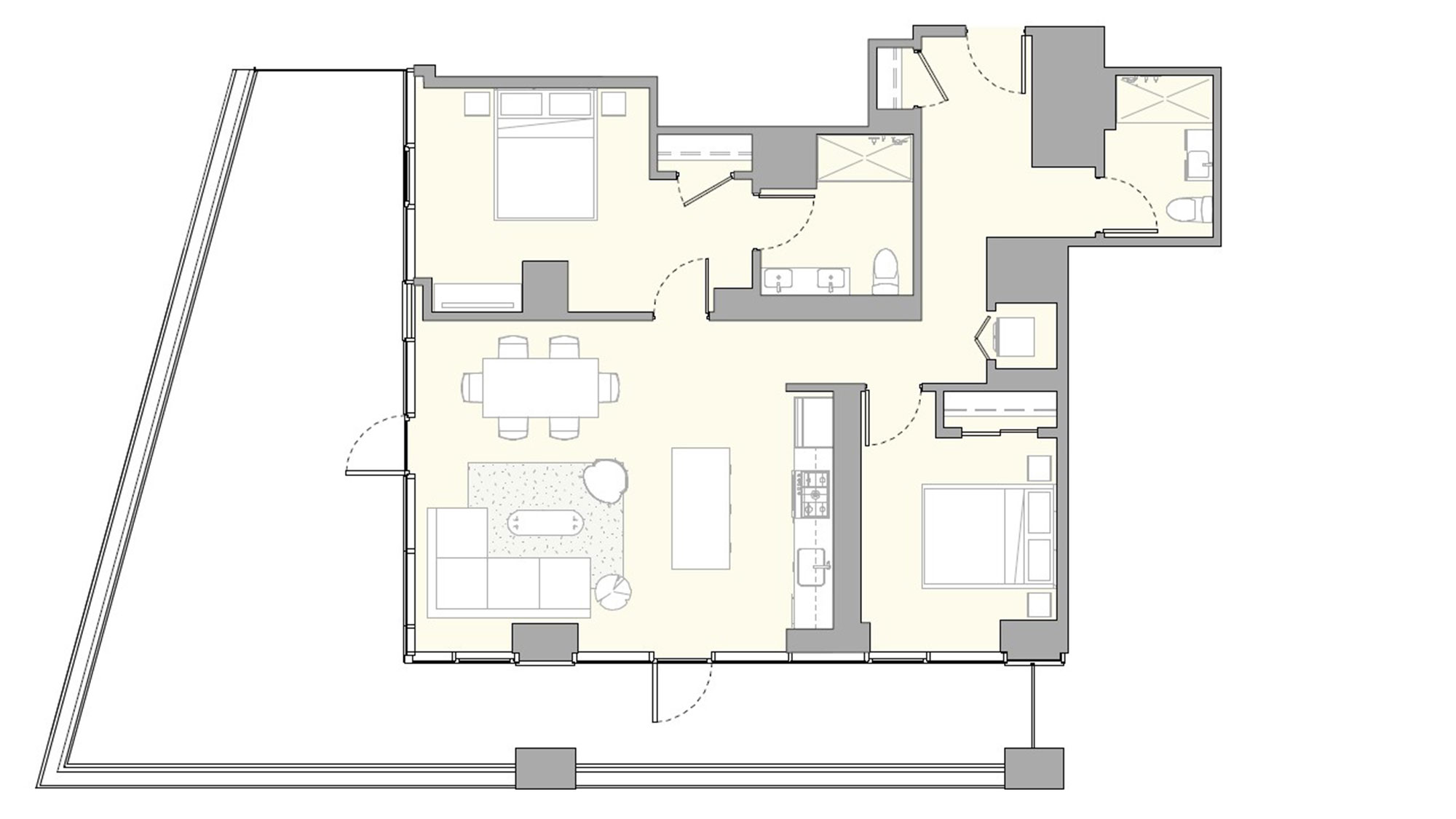

With a combined living and dining room and open-plan kitchen that opens directly onto a wrap-around private terrace, Penthouse Unit C is ideal for the social seeker interested in entertaining and connecting to the outdoors. With a living room accommodating multiple seating types and enough space for formal and informal dining spaces, this unit’s living areas are primed for a busy social atmosphere. The terrace wraps around the entire apartment and is accessible from both bedrooms, as well as the living-dining room. This unit is not “private,” and that’s by design.

Flexible and Unprogrammed Spaces

When designing residential developments for diverse residents, flexibility is key to giving residents a sense of ownership over their space. One way to achieve this is by adding an extra room with no designated purpose, often called a “den.”

The “den” — typically 80-120 square feet of unprogrammed space — represents minimal additional construction cost while expanding a unit’s target demographic. We’ve found that homes containing undefined spaces allow residents to more fully customize and personalize their living spaces.

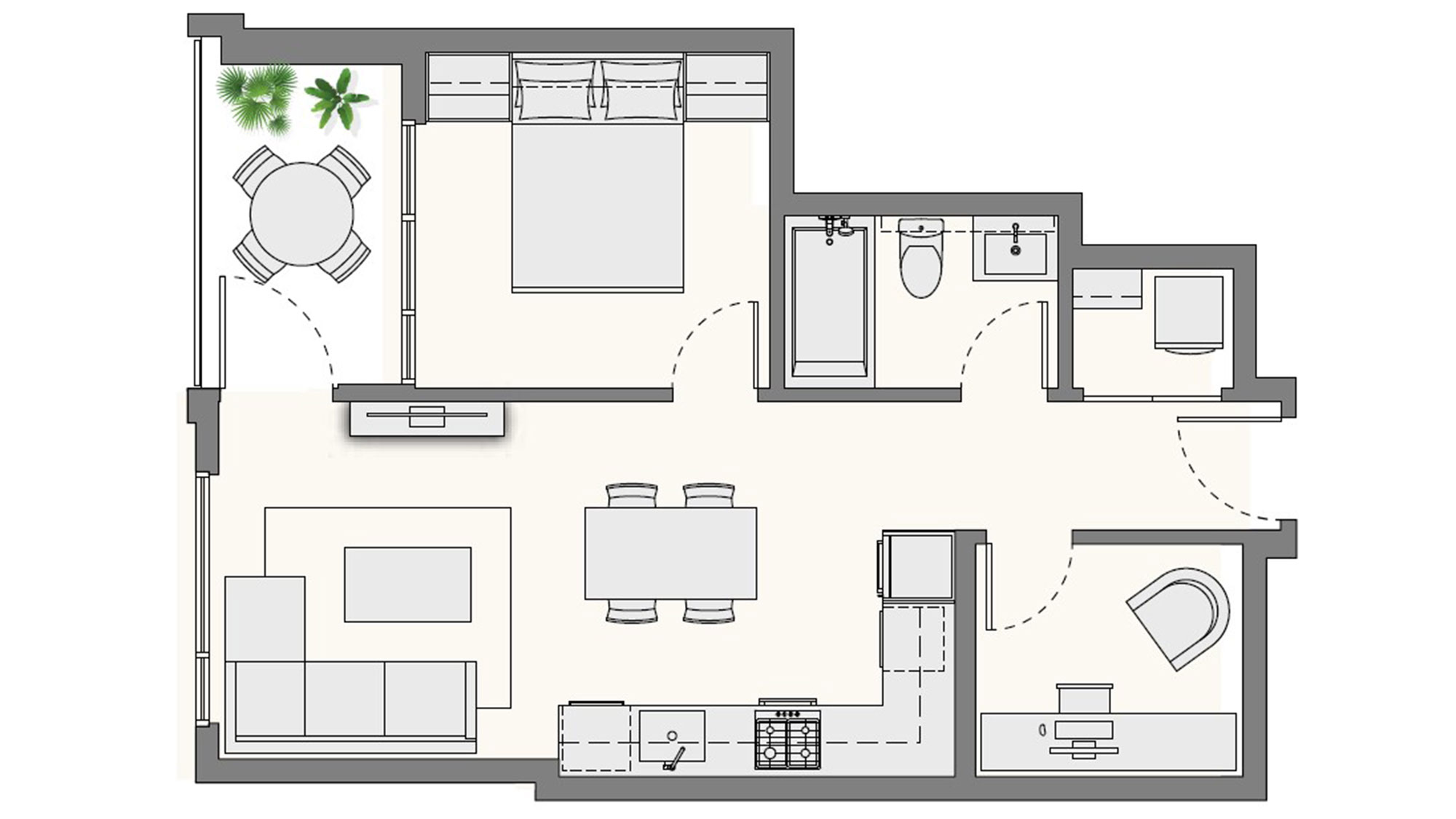

One recent example, Central Park House in Vancouver, shows how prioritizing unit design can lead to units that better reflect how residents live in their homes. In Central Park District in Burnaby, Gensler transformed the traditional high-rise condominium typology into a bespoke urban sanctuary. Central to that approach is the inclusion of a “den” across several unit types.

In one of the tower’s two-bedroom models, the centrally located den offers residents a naturally lit space to adapt as their needs evolve over time. The den could easily be transformed into an art studio, a dedicated pet area, a children’s study area, or a home office, making it marketable to creative professionals, families, and remote workers. This flexibility gives residents a strong sense of ownership over their homes and greater satisfaction with their living arrangements.

A Roadmap for Developers

As cities grow denser, flexible and intentional unit design becomes essential to creating livable homes. Gensler’s research highlights how adaptable spaces and thoughtful planning transform housing into homes that residents choose to stay in. Models like Pearl House and Central Park House provide a valuable roadmap for developers who prioritize both performance and resident experience.

For media inquiries, email .