Designing ‘the Quiet Airport’ at SFO

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) is helping to ease the passenger experience through hospitality-driven, inclusive design.

As peak travel season gears up, air traffic is higher than ever, and the Federal Aviation Administration expects the busiest summer since 2020. With news headlines about staff shortages, incidents at major airports, and long lines in security with REAL ID requirements, many travelers are feeling anxious about air travel.

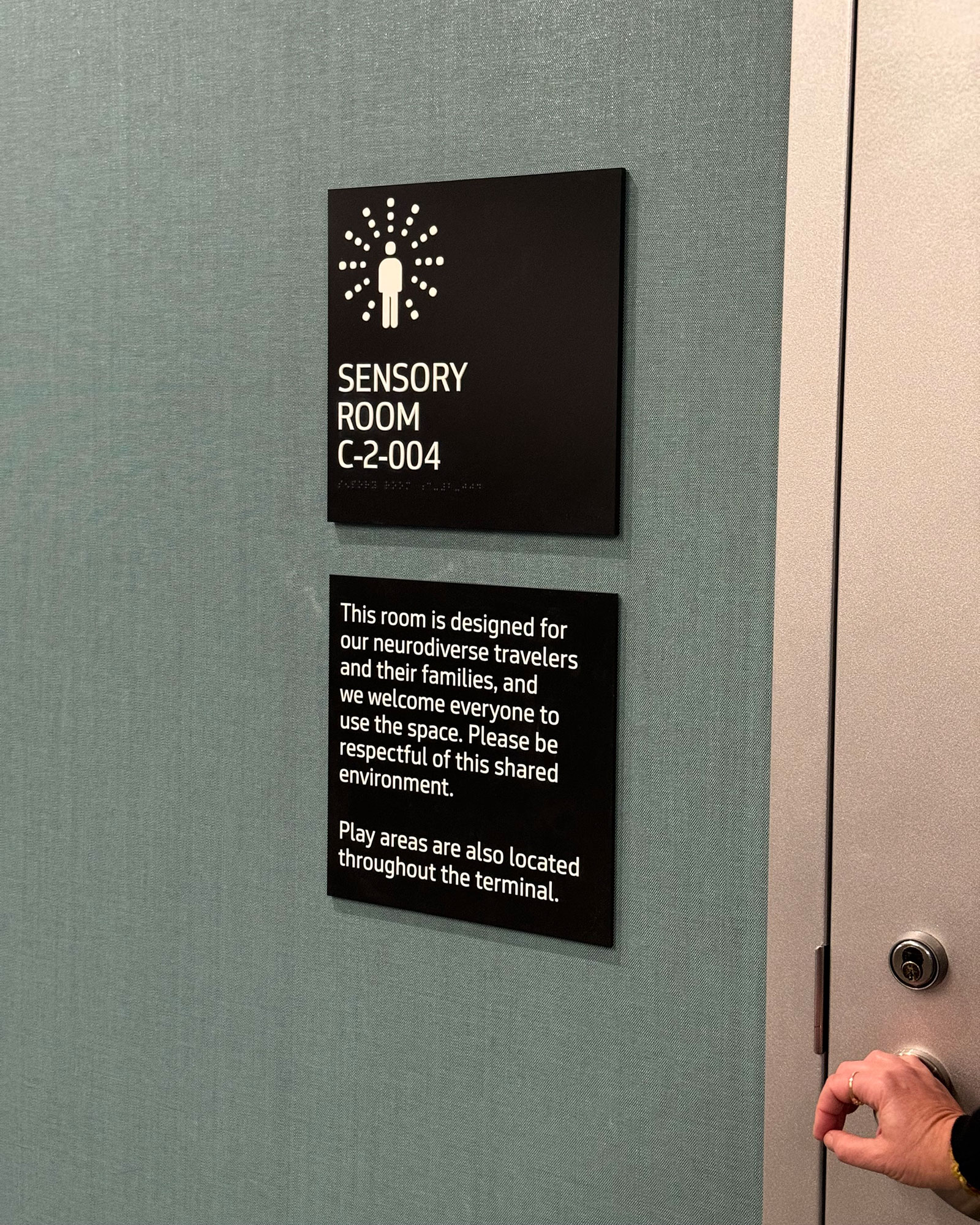

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) has long been a leading benchmark for other airports. Now, the airport is helping to ease the passenger experience through hospitality-driven, inclusive design, including a new sensory room for neurodiverse travelers — the first of its kind in the San Francisco Bay Area and the second in the state.

We spoke with Melissa Mizell, design director; Ryan Fetters, design director and Aviation leader; and Mark Santa Ana, designer, about how SFO is improving the passenger experience and furthering its reputation as a “quiet airport.”

Melissa, you’ve worked on every terminal at SFO. Could you talk about what SFO is doing differently and how it’s leading the way for other airports?

Melissa: Gensler has been working with SFO since the late 1970s. From the moment that I started working with SFO in 2008, I’ve experienced firsthand how they’ve always been very interested in creating a passenger-centric space. Every space within the airport should feel like a first-class club lounge.

With every terminal we’ve worked on at SFO, we’ve learned a lot from our workplace practice in providing choice and a variety of settings for people — from comfortable seating areas for nervous travelers to social spaces for people traveling in groups to people working while in the airport — and that has set a trend that other airports have started to follow.

We’ve also intensively examined our restrooms, using lighting that makes you feel good and expanding the suite of offerings — from providing a changing room to additional spaces for moms with children — and every time we do a terminal, we build on what we’ve learned.

Melissa: The term “quiet airport,” from SFO’s perspective, is not bombarding people with constant PA messages everywhere. So, we worked with an acoustician to make sure that all of the finishes and soft areas, combined with hard areas, contribute to that overall quietness. How is the airport making the travel experience less stress-inducing?

Ryan: When we started the Terminal 1 project, the design team worked with a more hospitality-driven spectrum of passengers during the visioning process. We used a lot of biophilic design principles to create spaces that are both auditorily and visually quiet, to create more of a sense of place, as well as a sense of grounding before getting on an airplane to go somewhere. This is San Francisco City & County International’s airport building, so they tuned the system so that a gate announcement only happens at the gate you’re at.

Mark: There isn’t a lot of clutter at SFO compared to other terminals. They also have a really fantastic art program that slows people down, and you have all of these spaces where you can experience quietness and enjoy the art before you go on your flight.

Mark: SFO prioritizes taking care of their passengers and employees, but there’s a business case behind it as well. Can you talk more about how a “quiet airport” is also good for business?

Ryan: As you bring stress levels down and satisfaction levels up, there is a direct correlation with how much money people will spend on concessions and other items at the airport. SFO has built its business model to share those concession profits between itself, the concessionaires, the city, the county, and the airlines. That’s their leverage to take on debt to continue their construction of new terminals.

So, it’s this virtuous cycle. As a passenger, you’re probably going to be a little bit less stressed out about getting to your gate, so you’re going to buy that cup of coffee and a magazine or book for your flight. That, in turn, helps strengthen their ability to fund new projects. And it’s a calmer environment to be employed at the airport, so everyone benefits.

Melissa: How have airports like SFO embraced inclusive design and neurodiversity, and are you seeing it in other parts of the world?

Ryan: Neurodivergent, sensible design cues have been around for a long time in certain typologies, such as education, especially in the U.S. This goes back to the 70s or 80s. When the real kickoff to neurodivergent design processes started, it originally leaned towards things like play areas or discovery zones. Now, places like airports are realizing that inclusive design affects people across all ages and spectrums of society.

Airports have started to see a massive uptick of passenger numbers because the price of entry to flying has decreased quite substantially over the past 20 years or so. People who have a disability or are on the neurodivergent spectrum who might have self-selected out of travel in the past are now starting to travel more often. And air travel can be a really big stressor for people in that position.

The first documented version of a sensory room-type element in an airport was in Atlanta in 2015 or so. Now, Pittsburgh and Seattle-Tacoma airports both have one, and there are a few internationally, so the uptick has been very positive within the industry.

Ryan: SFO is guest-centric and focused on being inclusive of all people and abilities. Therefore, they saw an opportunity to offer this type of experience to their passengers. Mark, can you talk about the process that went into developing the sensory room for SFO Terminal 1?

Mark: Our project had three different areas of focus. We needed to make sure that the space would be open to everyone, so we created an active area. We also designed a passive or quiet area where someone can decompress. On the other hand, we have all these activities for someone who is more hyperactive and wants to spend that energy. Finally, we created a space for travelers to acclimate themselves to what an airplane cabin would be like.

It was nearly a two-year project from start to finish. We also consulted with experts in the field who work with neurodiverse people. We also had parents who gave us pointers and comments on our design.

Mark: Ryan, as design director, can you talk more about how we designed this space for and with this diverse community?

Ryan: We worked with a group called Ark. They consult people who are building spaces like this, whether in public, education, the workplace, or other settings. Many of them either are on the spectrum or have family members who are, and that helps inform the design as well.

While we’re designing a quiet room where passengers can relax and tune out, that’s actually really difficult for a large portion of the population who actually need hypersensitivity and overstimulation to make themselves feel centered. And so, the sensory room is not about just calming down; it’s about centering yourself within that space. We wanted to make sure the space was more inclusive than just designing for a singular set of people on that spectrum.

Mark: Is this particular to the U.S., or have you seen any similar signals in other parts of the world?

Ryan: It’s becoming a lot more common, specifically in Europe. The U.K. has a program called Sunflower that will help certify all sorts of spaces, like a supermarket, workplace, or airport, where someone who wants to go to a place that can support them with their disability will receive a lanyard with sunflowers on it, and then, the location that they’re going to will be prepared to understand that the person might need some special assistance.

SFO is working towards getting some of the certifications for that program. Part of that would be working with TSA to allow passengers to come through security on a reservation basis so they could actually come out to the sensory room to test out the process of getting on an aircraft before coming to the airport, so they can take time to process what they’re going to be experiencing when they travel.

Melissa: Every time we’re in the sensory room, either a parent or a user approaches us and thanks us. They wish every airport had this space. What additional feedback have we received?

Ryan: The sensory room opened in November 2024, so while the airport is starting to collect some quantitative data on it, we’ve received lots of qualitative feedback. You see people who need the space for themselves, but you also see companions of people who benefit from it just as much. For example, a woman came into the sensory room with her adult son, who had some anxiety, and he saw the motion-activated screen and was getting some of that energy and nervousness out of his system. And his mom was sitting in the rocking chair, experiencing a moment of quiet.

Ryan: Every time we work with SFO, we try to build upon what we’ve learned. Melissa, can you talk about how we’re using these insights to inform the design of other terminals?

Melissa: We’re designing the next iteration of the sensory room in SFO Terminal 3 West with some of the more informal lessons we’ve learned from Terminal 1. We’re making it bigger. We’d like to include more of the airplane in the cabin, so that you can experience what’s it like to go through the door, and we’re thinking about having a quiet area outside for somebody who needs a moment, be it a child or be it an adult, just to pull aside.

Ryan: You’ve said the next Holy Grail is about fostering happy employees. Can you elaborate?

Melissa: Improving the airport employee experience is not about providing yet another amenity. We’re working on giving employees more conveniently spaced breakrooms, so they don’t have to rush for a 30-minute lunch break. They also have a choice and variety of furniture and wellness areas. It’s just another example of SFO’s extreme focus on people.

For media inquiries, email .