How Local Governments Are Transforming Green Building Policies — and How to Prepare

August 18, 2022 | By Emily Low and Abram Goodrich

The U.S. government’s recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 includes unprecedented investments in green buildings, including rebates and incentives to ensure that buildings are highly efficient and resilient. It would be easy to assume that this forward-looking legislation applies only to new buildings, but some of its most important provisions are actually aimed at providing pathways for existing buildings to assess tax deductions for retrofits.

The reason why lies in a simple mathematical reality: The majority of the buildings that will exist in 2030, and even in 2050, have already been built. So, while the sleek aesthetics and impressive performance metrics of new buildings are important, they won’t get us to carbon neutrality by themselves. From a climate action point of view, the architect’s function has as much to do with breaking new ground as it does with managing, altering, and evolving what we already have.

On the local level, as cities around the world tighten their metaphorical carbon belts, they are directing their attention at existing building stock. This is a conversation distinct from that of changing building codes. Whereas building codes dictate new construction, building policies — such as performance standards — pertain to structures that already exist. It thus falls to building owners and property managers to ensure that their assets meet the new requirements, typically centered around energy performance, efficient resource usage, and reduced carbon emissions.

With new policies emerging seemingly every month, it can be difficult to get a handle on what is required of whom. Here, we offer a primer on where these policies came from, what they mean, and where they’re likely to go in the future.

The pioneer: Washington, D.C. and its Building Energy Performance Standard program

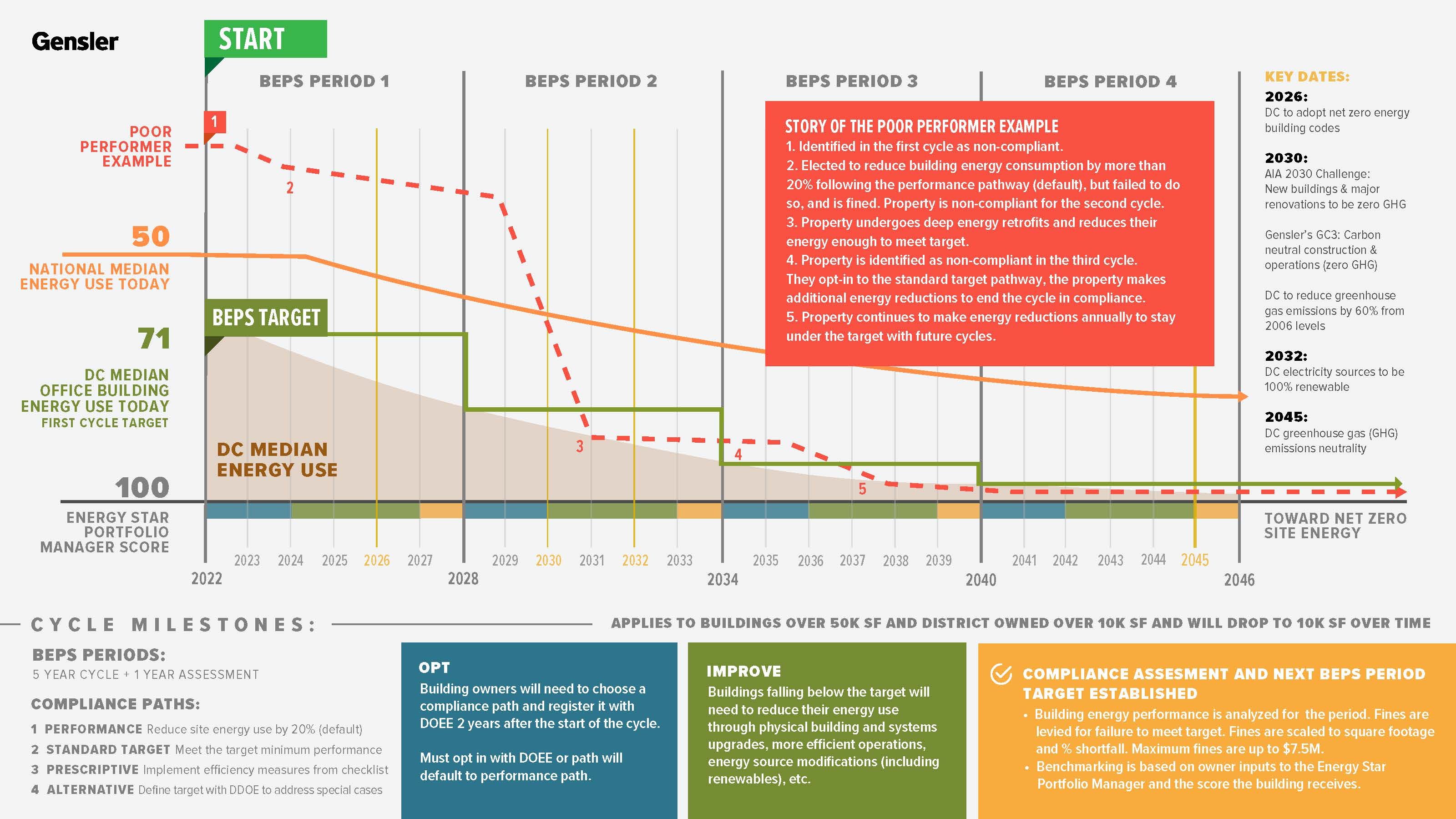

When the District of Columbia’s local council passed the Clean Energy DC Omnibus Act in 2018, it established the nation’s capital as a trailblazer with respect to climate action reform. A significant part of that legislation and its stated goal of cutting the District’s greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2032 is the Building Energy Performance Standard (BEPS). Now in effect, this policy takes an existing benchmarking program, based on the Energy Star Portfolio Manager, and adds a minimum score that buildings over 50,000 square feet will have to achieve. The District’s policy was the first of its kind, establishing new sustainability performance targets for each building type — even buildings with historic designations. The program starts with larger buildings but will eventually cover all privately-owned buildings over 10,000 square feet.

What the BEPS policy essentially comes down to is that buildings must meet the target scores or face fines set at a maximum of $10 per square foot of gross floor area, capping out at $7.5 million. To avoid penalties if a building falls short, several compliance pathways exist to guide it through energy consumption reductions over time. Compliance cycles last six years, with buildings identified as non-compliant at the start of the cycle having five years to make improvements. The district uses the sixth year to access how much buildings have improved and set the updated performance standards for the next cycle.

The District of Columbia Department of Energy and Environment maintains a publicly accessible database mapping every project covered by the BEPS program and whether it is considered compliant. Third party verification of compliance data is required every three years.

While it is currently based on the Energy Star benchmarking program that was already established, the District could transition to a carbon standard in the future, as other jurisdictions have done. The policies, in all likelihood, will function a bit like computer software, requiring periodic updates and refinements.

Jurisdictions are taking unique paths to sustainability

The Inflation Reduction Act comes at a fraught time for climate advocacy, especially in the context of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision restricting the EPA’s authority to regulate carbon emissions. Moving forward, it appears to be unavoidable that states and local municipalities will bear significant responsibility to address the issue. A consequence of this reality will be a high degree of variation in how individual jurisdictions craft their policies. For instance, while it was passed around the same time as Washington, D.C.’s BEPS Program, New York City’s Local Law 97 focuses much more heavily on greenhouse gas emissions.

In plain terms, the policy variation means that what is considered a high-performing building in one jurisdiction may not be considered high performing in another. Until natural gas is sunset in Washington, D.C. in 2026, a renovation there could benefit from an efficient natural gas based system, whereas one in New York would not. St. Louis has enacted a policy similar to that of Washington, D.C. But our neighbor, Montgomery County, Maryland, has taken the approach of letting building owners chart their own paths to net zero carbon emissions by 2035, opening the door to notable discrepancies among buildings only a few miles from one another.

Across the United States, comparable laws are likely to go on the books soon. Bipartisan infrastructure legislation passed earlier this year sets aside $1.8 billion to help local governments develop building performance standard policies. As of January 2022, there were 33 states and local jurisdictions that had committed to passing policy targeting existing building performance by 2024. Even at this early stage, these commitments encompass one fifth of U.S. buildings.

To navigate the new policy landscape, it will be crucial for architects and building owners to work together

When Gensler launched its Cities Climate Challenge (GC3) in 2019, many of the sustainable design practices for which we advocated were still optional. Now, in more jurisdictions, that is no longer the case. While glad to see that our resilience commitments anticipated new policy, we recognize that the task building owners and property managers now face is not easy. Recently, for several clients in the Washington, D.C. area, we have developed specific plans to address the BEPS Program, evaluating what in a client’s real estate portfolio is working and what is not.

At the bare minimum, every architecture, design, and real estate consulting project should evaluate opportunities to get a building closer to compliance — or keep it there. Even buildings in compliance should look toward the future when making systems upgrades. No building owner wants to replace a mechanical system before the end of its lifespan because it isn’t efficient enough for future compliance cycles.

Architects are well versed in deep energy retrofits, and we are witnessing countless opportunities for significant emissions improvements on even the most minor repositioning projects. It only makes sense to consult with multiple parties as early as possible in the process; establishing a strategy for compliance, for example, should not be done solely with an MEP Engineer. As architects, we can use the engineer’s models and recommendations to develop a capital expenditure plan that will connect at the building’s position in the market and changes to zoning and codes to energy improvements that will keep the building in compliance.

Forecasting across a longer time horizon is important because as performance standards continue to evolve, they will only seek more efficiencies over time. Climate resilience, after all, is a moving target defined by what technology is capable of at any given moment in time.

All things considered, it is best to think of policy programs like BEPS as opportunities rather than burdens. Sound building performance, after all, can have several effects on the positive side of the balance sheet, including reducing energy costs, increasing rental demand, and improving experiences for tenants. It is also an opportunity for landlords and tenants to work together. New tenant fit outs can improve a building’s energy usage intensity (EUI) while helping an organization meet its ESG goals and carbon commitments. Embracing such opportunities may ultimately be what moves the needle within the sustainable building conversation and reminds us of how much good we can do with the resources already at our disposal.

For media inquiries, email .