Reimagining the Future of Cities as Healthy Cities

July 01, 2020 | By Nayan Parekh

Editor’s Note: This post is part of our ongoing exploration of how design is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As the world continues to grapple with the coronavirus, none of us know what “post-COVID” truly means, or what it really looks like, or when it will be here. Will we go back to pre-COVID normal? Or will this moment accelerate positive changes to the built environment that can benefit our urban communities?

Urban planning is primarily about the design of systems, and historically the health of urban populations has been intrinsically bound to the practice of urban planning. Cholera outbreaks in London in the early 19th century created improvements in sanitation. Tuberculosis in New York in the early 20th century led to improvements in housing regulations and public transit. SARS in Asia led to upgrades in medical infrastructure and systems to monitor and map the disease.

Epidemics have shaped our cities for a long time. The key question in this moment is, how can we use what we’re learning to improve the quality of life in cities after COVID-19?

As I see it, we have three key opportunities to change urban infrastructure and create the foundations of new, healthy cities.

1. Practice more polycentric planning.

At the core of what makes dense urban environments authentic, desirable, and attractive is a network of forces that create unpredictability, serendipity, and diversity. All qualities that in this time of social distancing appear to be a threat to our personal safety and well-being. How can cities be made stronger by reconsidering the nature of density and its vital relationship to public health, wellness, and resilience?

The polycentric model could be an answer. In this type of plan, self-sufficient districts are distributed across cities and function like independent urban villages.

Singapore has had a polycentric planning model in place for a while, but we are seeing much more rigor around this thinking across the world now too. Paris, for example, is looking to implement the “15-minute city” in which residents’ needs — from work to shopping and leisure activities — can all be found within a 15-minute walk or short bike ride from their homes. In the U.S., cities such as Portland, Detroit, Dallas, and Chicago are all exploring versions of the 15-minute, or in some cases 20-minute, city.

By planning for local, integrated mixed-use districts, we can create potential for healthier, safer, and more connected communities.

2. Layer in more digital experiences.

Many office buildings have already begun to leverage digital tools such as heat-sensing cameras that can scan body temperatures. But there are many more digital possibilities that can help promote health and safety in our cities.

Imagine a continuous scanning of our patterns and preferences through the spaces we navigate. The sensors in the spaces know that it’s you. At the office, for example, they set the desk to the correct height, adjust the lights, tune the temperature to suit your preference and tell you when the desk was last cleaned.

At the urban scale, integrated digital mapping already helps manage streets and roadways during rush hour. This could be expanded to help manage other public spaces and help promote neighborhood activities.

With COVID there has been a shift away from crowded public transportation and a rise in the use of personal mobility devices such as e-bikes and e-scooters. Electrification in the auto market also breaks down traditional barriers between architecture and roads. Electric cars will be able to mix with other program uses allowing for new place typologies and better use of car-centric space.

With next-generation transportation options like autonomous vehicles on the horizon, we are still at the onset of this paradigm shift that will present wide-ranging opportunities for urban planning.

It’s not hard to imagine all these disparate technologies and systems coming together as part of a design strategy for a post-pandemic world so that people navigate spaces comforted by the fact that they’re safe where they are.

3. Recommit to sustainable and resilient design solutions.

While a shutdown and the resulting economic crisis is not a productive way to achieve cleaner air, cleaner water, and a greener world, it does provide an opportunity to remind everyone that there we have shared global experiences and that we can reposition our mindsets on sustainable behavior going forward.

Here are some areas we’re focused on to help promote sustainable approaches within the design and architecture industry:

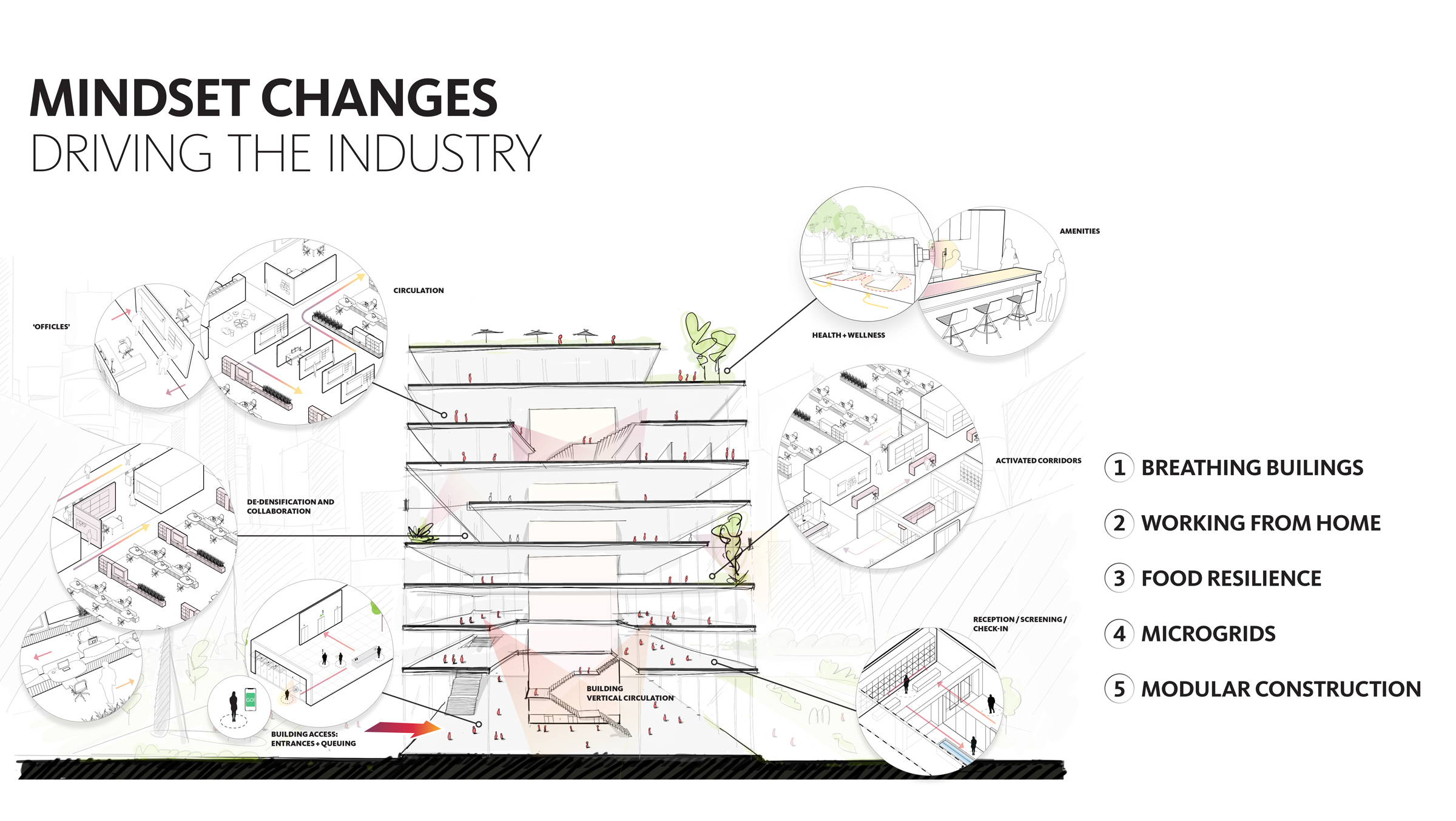

- Breathing buildings: The pandemic has sparked new conversations in the industry about breathing facades and HVAC systems now that we know the introduction of fresh air not only helps maintain healthier environments, but also dilutes the human-to-human passage of airborne elements.

- Working from home: While the jury is still out on the global work from home experiment, initial findings point to a hybrid model for the future of work – where we spend part of our time working at home and part in the office. This will change how office spaces are designed and used and will force repositioning of single-use buildings in city centers. It will likely also impact the design of the residential projects in the future as people’s home needs shift.

- Resilient food systems: Food resilience is a major focus for the future, especially in countries like Singapore where 90% of the food is imported. Agrotechnology is enabling the conversion of factories and warehouses for commercial indoor farming to produce vegetables, meat, and even milk. Integrating urban farming into building systems at all scales — on facades, allotments in parks, atriums, terraces, etc. – will help increase overall self-sufficiency but also create awareness about food resilience amongst urban dwellers.

- Utilities: The pandemic has also reignited discussions about “microgrids” — which provide targeted, flexible, and efficient utility services to districts that can both connect and disconnect from the traditional grid as physical or economic conditions might warrant.

- Modular construction: Fabricating and assembling building components offsite in contained warehouses could prove to be a healthier, safer, and quicker alternative to traditional construction.

As sports and entertainment arenas, retail centers, and faith spaces begin to open, and all of us emerge from our homes and begin to re-engage with our communities, the one thing we will be looking for is an underlying trust in the places and spaces into which we’re emerging. Creating a healthy urban experience requires aligning space, culture, interaction, and behavior. However, the biggest challenge ahead is finding ways in which design can rebuild trust and communicate clearly how health and wellness well-being is considered in the built environment.

For media inquiries, email .