The Future of Travel? Start With the Future Traveler.

March 09, 2023 | By Jennie Santoro and Melissa Mizell

Millions travel through airports each day with a diversity of needs — and ever evolving needs — enabling airports to be at the forefront for continually improving inclusive design strategies.

The ever-expanding spectrum of travelers

Together with our colleagues in workplace and education design, we have been exploring the meaning and application of inclusive design in our practice and have come to realize that airport environments encompass one of the most demographically, culturally, and physically diverse sets of users. Airports must make everyone happy. Airports look to connect us to a local sense of place to welcome us home while simultaneously welcoming people from every culture from every corner of the globe.

The aviation market continues to recover from the pandemic with steady passenger growth. As that group of travelers continues to grow, it also becomes more diverse. And as society changes, so does the traveling public. The impacts of the pandemic on aviation go beyond health regulations and travel numbers. How people live, work, and play has changed and so have their travel habits. For many, the answer to “business or leisure?” is now “yes.” Hybrid work, work from anywhere, and digital nomad are the latest buzzwords impacting passenger behavior and needs.

The world is also growing older. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that by 2034 that older adults (those over 65) will outnumber children (those under 18) by 2034 and the World Health Organization predicts that by 2030, one in six people in the world will be 60 and over. The needs and desires of passengers are changing, and we must start by understanding them.

Empathy as a design tool

As both travelers and their needs evolve, so must our thinking and approach. For decades, airport designers have used passenger types or personas as a tool to think through the passenger journey and the variety of user needs. While personas are a useful design tool, they also have their limitations, often overgeneralizing and putting people in boxes.

An alternative approach is to think about mindsets. A “mindset” envisions the needs and desires of a person or group on a specific journey. Instead of placing labels on people, it identifies needs based on scenarios. The same person may travel very differently alone on a business trip than when traveling with their family. Even on the same journey, a frequent domestic traveler may seek a different experience when traveling through their home airport than in an airport halfway around the world in a country they are visiting for the first time, where they don’t speak the language.

This way of thinking also challenges us to be open to the unfamiliar, be inquisitive about new needs, and find intersectionality rather than rely on stereotypes. To provide insights on the user experience, these “mindsets” should be informed by data — both quantitative data from airports and airlines, as well as qualitative data from surveys and stakeholder outreach sessions. An inclusive approach is the foundation for inclusive design. Leading with empathy for one user’s needs, our design solutions often address the needs of many.

At San Francisco International Airport’s recently renovated Terminal 1, both binary and gender inclusive restrooms are offered to travelers. During the design process, the team engaged with focus groups comprised of families and parents of young children, caregivers, and those needing assistance in restrooms, as well as LGBTQ+ users and representatives of the transgender community. As a result, all users, regardless of gender identity, have access to single-stall facilities that accommodate both privacy and safety, with signage and icons that are inclusive and universally understood.

Moving from prescribed experience to choice and empowerment

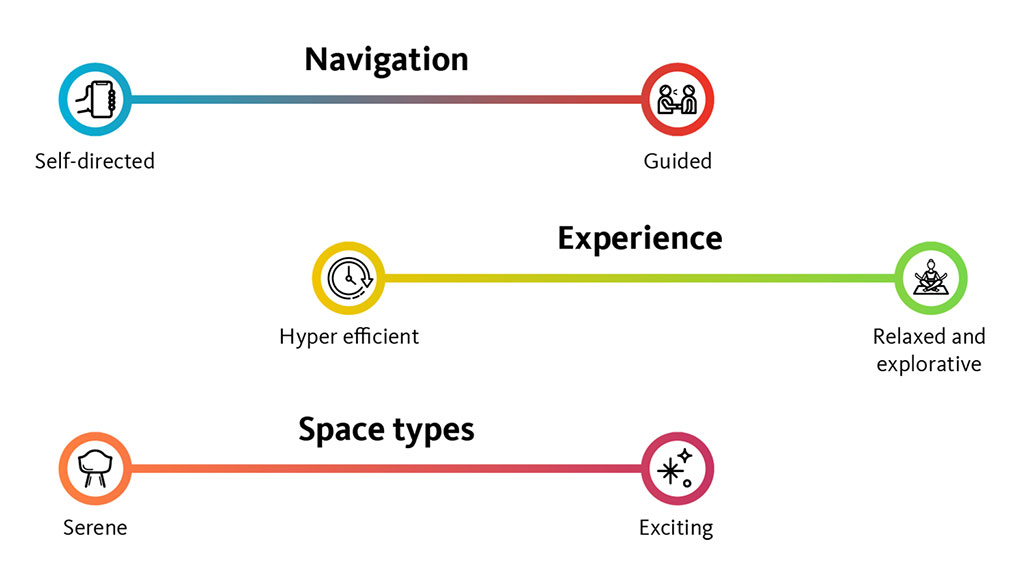

There is so little that a person has control over when they travel by air. The romanticism of air travel from a bygone era was replaced by airports as passenger processors, trying to push people through facilities that couldn’t keep pace with the growth of air travel. As we update aging infrastructure or build new facilities, we’ve shifted our focus to the passenger experience. However, that experience cannot be singular. Airports must get you to your destination while also allowing you to enjoy the journey. And what defines an enjoyable experience varies with each individual and their “mindset” for that journey. What if we replace a prescribed experience with the ability to choose your own adventure? What if we give back more control and provide a spectrum of choice?

Break down barriers

When the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law in 1990, it changed the way we design spaces, but 33 years later, it is considered the bare minimum. Universal Design principles help expand our approach to incorporate a wider range of abilities, sizes, and ages. Research into neurodiversity is also helping us to appreciate the many ways humans perceive and process sensory inputs. The “surprise factor” in airports is best for moments of art, entertainment, and diversion, not in systems and processes — predictability is key for reducing stress. Stress-free travel requires clear, unambiguous information delivered when a person needs it. Excellent wayfinding and signage should be coupled with audial, visual, and tactile cues, as well as built space that encourages an intuitive flow.

Finding barriers in the built environment is a constantly evolving process, and only by including diverse stakeholders in the design process and revisiting and questioning our “best practices” can we pave the way for truly inclusive airports.

Happy employees = Happy passengers

Airports are complex ecosystems. Everyone who works at an airport, either passenger-facing or behind the scenes, has an impact on the traveler journey. Applying inclusive design principles to staff spaces and taking care of airport and tenant workers, airline employees, maintenance and janitorial staff, mobility assistants, and volunteer staff improves their lives and benefits passengers. And happy passengers spend money and return to the airport repeatedly. Good terminal design is design for all.

For media inquiries, email .