Designing for Collective Memory and Intelligence in the Workplace

How your workplace can unlock collective intelligence for smarter, more connected teams.

In 1906, 800 townspeople in Plymouth, U.K., guessed the weight of an ox at a county fair. When a man named Francis Galton analysed the responses, he found that while most guesses were way off the mark, the average of the crowd’s responses was within one pound of the actual weight of the ox. The group was smarter than its individual members.

What if the workplace, like that county fair, is an environment where teams reliably outperform the individuals in them? What if the workplace is where we cultivate our collective intelligence?

We’ve learned more about collective intelligence since Francis Galton. Dr. Anita Woolley of Carnegie Mellon found that one of the key drivers of collective intelligence is collective memory. And interestingly, one of the best memory storage devices we have is space.

The Memory Palace

Competitive memory champions understand the power of space to store information. They use a technique called the Memory Palace that uses imagined locations to store and recall information. They use this technique to memorise digits of pi, the order of cards in a shuffled deck, or the names of strangers.

Now imagine if our workplaces could be a communal Memory Palace, a physical repository of the collective learnings of everyone in it. If we design a workplace where knowledge, experience, and memory can be stored, shared, and exchanged, we can create an environment where collective intelligence can flourish.

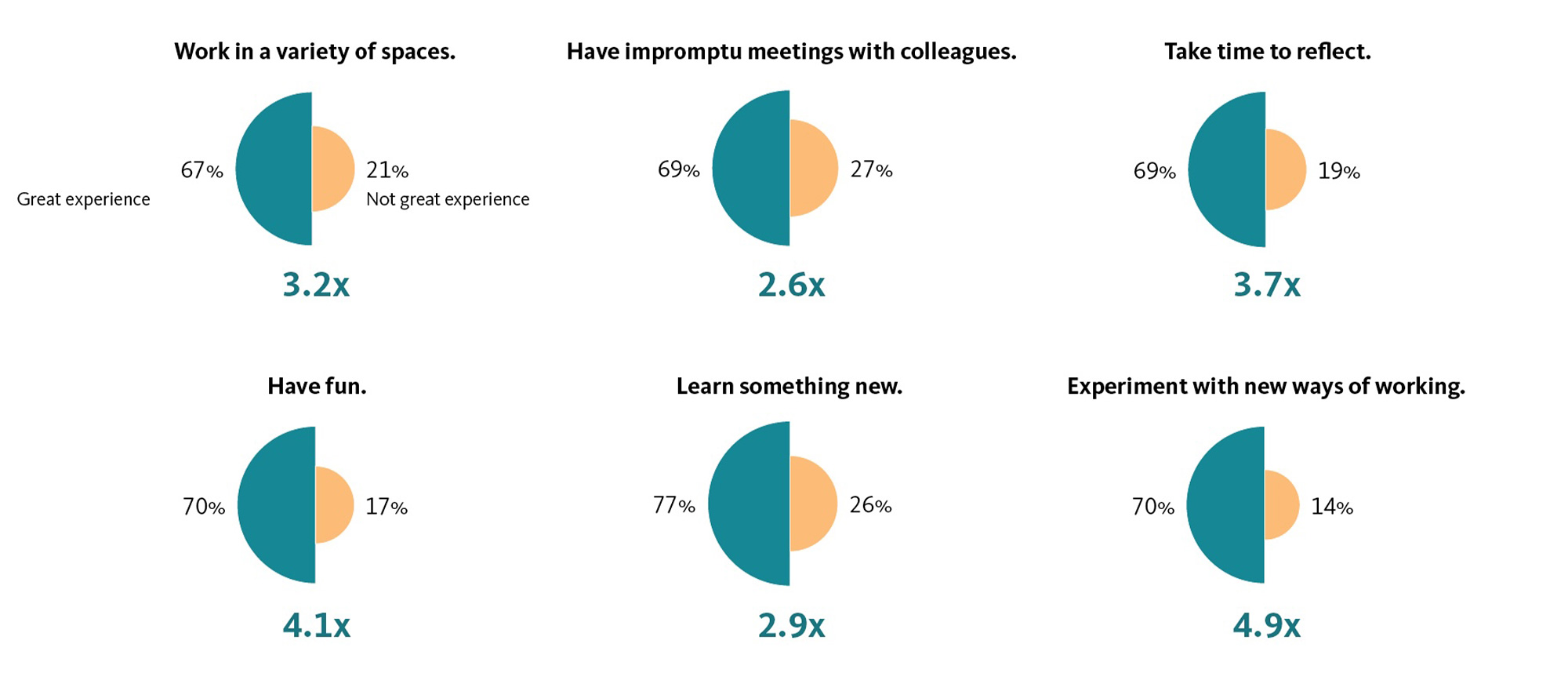

We see signs of high collective intelligence in the highest performing workplaces. In our 2025 Gensler Global Workplace Survey, we found that people who have a great workplace experience were almost three times more likely to learn something new, 3.6 times more likely to think about something in a new way, and almost five times more likely to try something new (or new to them).

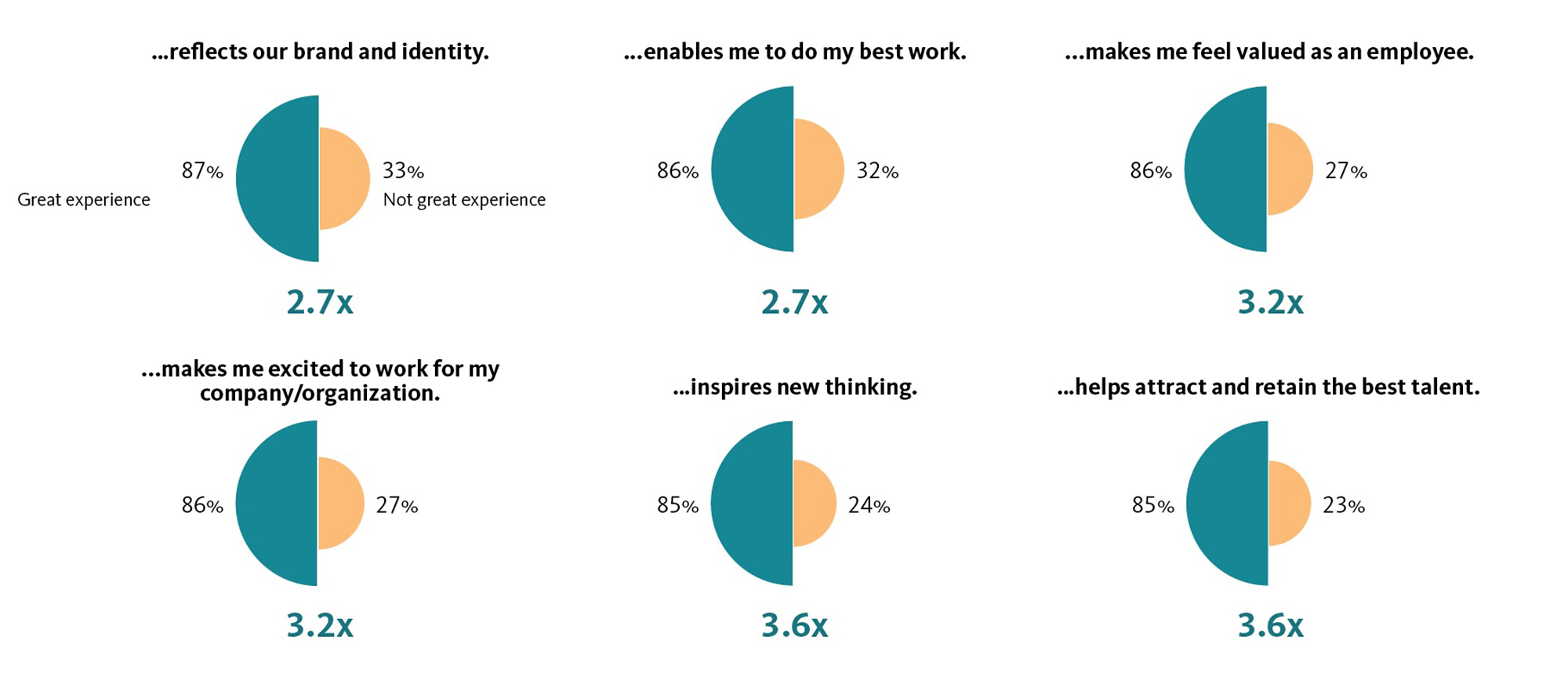

The overall design of the office environment...The percentage of workers who agree with each statement, segmented by those who strongly agree their workplace provides a great experience and those who disagree or feel neutral.

Source: 2025 Gensler Global Workplace Survey

How often do you do the following at the office? The percentage of respondents who do these activities often or very often, segmented by those who strongly agree their workplace provides a great experience and those who disagree or feel neutral.

Source: 2025 Gensler Global Workplace Survey

How do we design a palace of collective memory?

There are three main ways we can design for collective memory and intelligence:

- The setting: When memory champions select a Memory Palace, they imagine environments that are meaningful — places to which they have an emotional connection.

We do the same when we design memorable workplaces, as we did for the London HQ of the biscuit and confectionery company pladis. Bringing together multiple brands under one roof, we knew the setting that would unite them all was a kitchen. A kitchen reminds every employee, regardless of brand, of why they do what they do: the joy of feeding people, and the memory of past kitchens.

- The story: Memory champions don’t just imagine a playing card or a number sitting in their Memory Palace — they come up with a story about it. Instead of the Queen of Spades, they might imagine Freddie Mercury from the band Queen, playing a big shovel.

Designers also use storytelling to make places memorable. At Etsy’s HQ in Dublin, we commissioned local artists to knit acoustic panels. We learned that every village in Ireland has its own knit pattern, so that if sailors were washed ashore, they could be returned to their village. Every acoustic panel tells the story of a unique village, and the craft that brought its sailors home.

- The twist: And finally, memorable things are unexpected, surprising, even absurd, like Freddie Mercury playing a shovel.

Surprise and delight make our workplaces memorable as well. Wunderkind in New York occupied two floors that could not be physically interconnected. So, we installed a light fixture in the reception on the lower floor, which was — unexpectedly — the roots of a tree. The curious visitor might wonder why there are roots on the ceiling, and perhaps what lies above them. And what lies above them, on the upper floor, is the rest of the tree.

Why does collective intelligence matter?

First, teams with high collective intelligence build a shared culture. For what is culture if not our shared memories and experiences? As author Joshua Foer wrote, “Culture is an edifice built of externalised memories… Our memories make us who we are. They are the seat of our values and the source of our culture.”

Second, teams with high collective intelligence invent better ideas. In a shared Memory Palace, people can deposit their knowledge and their half-formed theories for someone else to pick up, carry forward, and combine with something unexpected. According to Joshua Foer, “creativity is, in a sense, future memory.”

And finally, teams with high collective intelligence make better decisions. In May 1968, the U.S. submarine Scorpion disappeared in the Atlantic. No one knew what happened to it, or how to find it. In the face of this impossible task, a naval officer named John Craven approached experts across a wide range of disciplines, from mathematicians to salvage experts, to offer their best estimate about where to find the Scorpion. Each of these estimates was wrong — but when Craven combined all the answers together, it pointed him to a location that was within 200 meters of where the Scorpion was ultimately found.

Personally, I don’t know how to solve climate change. I don’t know how to deploy AI in a way that captures all the benefits and avoids all the risks. But I hope that we — collectively — know these answers. At a time when humanity faces questions that are bigger, hairier, and more complex, the power of our workplaces to unlock our collective intelligence is more important than ever before.

For media inquiries, email .