Future of Cities

Redefining the future of cities as ecosystems of multiuse, multi-generational, 20-minute neighborhoods.

LATEST REPORTS & ARTICLES

Research

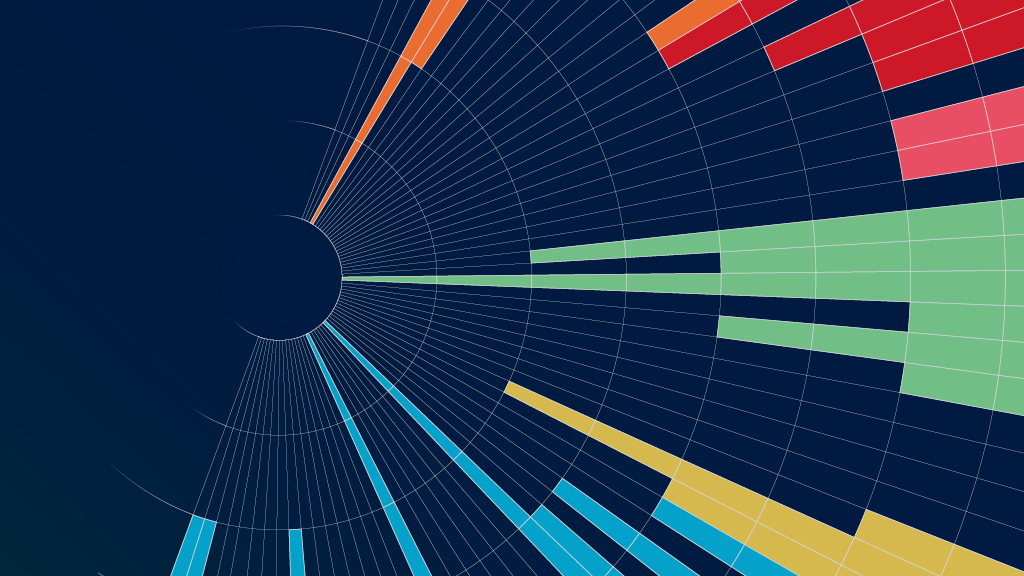

City Pulse 2025

Gensler surveyed 33,000 people across 65 cities to uncover what makes a city magnetic — how it attracts new residents and keeps them wanting to stay.

Blog

The Top 10 Cities People Don’t Want to Leave

Gensler’s 2025 City Pulse survey reveals the top cities where people not only move to, but also stay long-term.

Research

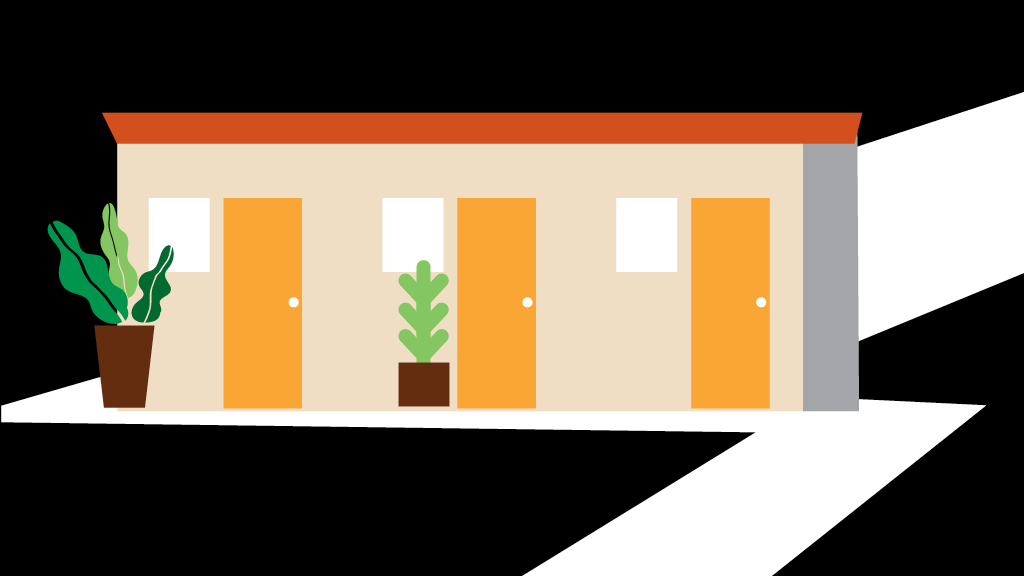

Ending Homelessness

Interim supportive housing, using small, prefabricated tiny homes on temporary sites, is presented as a rapid, cost-effective, and scalable strategy to address the growing crisis of homelessness.

Blog

The 20 Cities Attracting the Most Newcomers

New city residents often leave within five years. To remain successful, these magnetic cities must also engage and retain their new populations.

Blog

What Draws People to Cities — and What Makes Them Stay?

Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 research offers insights into the factors attracting people to cities and compelling them to stay.

Blog

How Cities Can Establish Resilient Communities

To mitigate potential damage and risk, cities can form resilient communities to proactively prepare for, respond to, and recover from a disaster.

Research

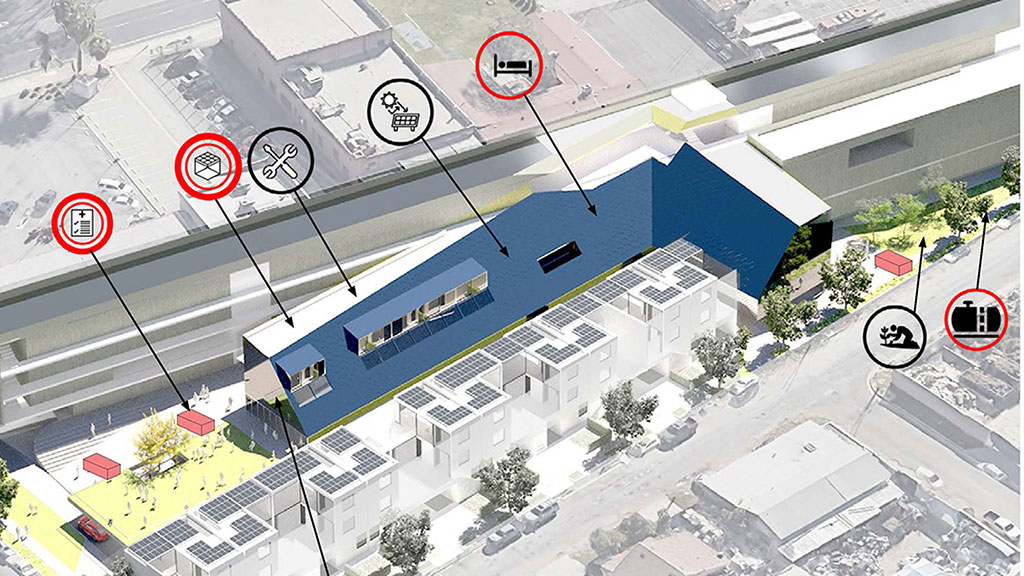

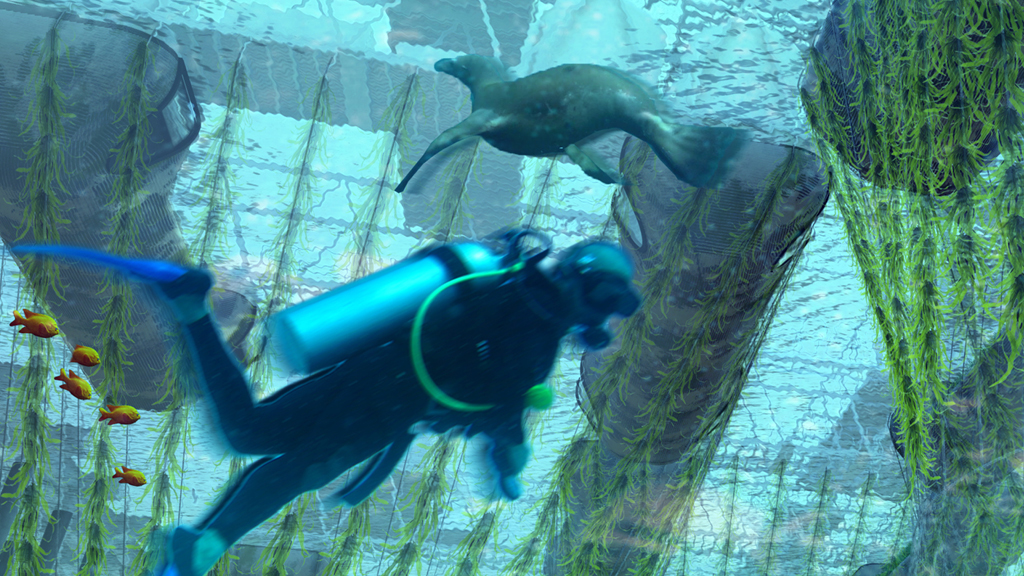

Designing Amphibious Structures

The design of amphibious, modular structures, leveraging existing port infrastructure and small components for sunlight penetration, offers a scalable solution to create new marine habitats and restore coastal biodiversity in disturbed waterfront environments.

Blog

Designing a New Future of Cities Through Wellness and Experience Design

How cities can take an active role in fostering healthier, more fulfilling urban lives for residents and visitors.

Blog

Creating a More Resilient Future With Green and Thriving Cities

As the demand for sustainable and liveable cities grows, urban planners and architects are adopting innovative strategies to harmonise built and natural environments.

Blog

Urban Air Mobility Is Here. Here’s How Cities Can Adapt.

Advanced air mobility is ready for launch. The next crucial step: preparing buildings and infrastructure to get this sustainable mobility solution off the ground.

Blog

A New Vision for Urban Design in Tropical Climates

Through thoughtful, climate-responsive design, seemingly adverse conditions can become a distinct advantage for tropical cities.

Blog

Urban Design’s Renaissance: How San Francisco Is Leading the Way

Cities everywhere are rethinking not just how they look and function, but how they can better serve the people who live in them. Few cities are as poised to lead this transformation as San Francisco.

Blog

Birmingham’s Renaissance: The City of 100 Quarters

How the city’s next evolution is embracing both innovation and heritage to shape a vibrant future.

Blog

10 Opportunities for a More Resilient and Equitable Jersey City

Listening to the local community to improve climate justice, health, safety, and equity.

Blog

Toronto’s New Deal Highlights the Importance of Healthy Cities

Here are three areas Toronto can focus on to bring people downtown, improve accessibility, and provide a better central business district experience for all.

Blog

Trends to Watch: The Future of Cities Relies on Multiuse Districts

Gensler’s Mixed Use & Retail Centers leaders discuss the opportunities shaping the future of cities and multiuse districts.

Blog

Designing Safe, Walkable Cities for Future Generations of Children

Thoughtful urban design can transform cities into vibrant, inclusive spaces where children can thrive, connect, and grow.

Blog

How Urban Design and Educational Spaces Can Combat Child Loneliness

Through thoughtful urban design, we can create inclusive, supportive environments where children can safely explore and learn outside traditional classroom settings.

Blog

Trends to Watch: What Other Cities Can Learn From New York City’s Conversion Boom

As U.S. cities experience high commercial real estate vacancy rates and housing shortages, developers have an opportunity to invest in and convert stranded assets.

Blog

How Life Sciences Developments Can Redefine Urban Areas

Sciences R&D developments are migrating to amenitized urban areas, unlocking opportunity for architectural innovation.

Blog

Trends to Watch: Building City Identities to Become Destination Brands

How can brand positioning and a compelling narrative help cities create global destinations and build strong brand advocates?

Research

The Return of the City

We examined how global perceptions have shifted from 2021 to 2023 across 15 global cities to understand the obstacles and opportunities facing cities today.

Blog

Trends to Watch Reshaping the Future of Cities and Urban Living

Gensler’s Cities & Urban Design leaders discuss what’s next for the future of cities.

Blog

Maximising Urban Space: 3 Strategies for Solving the U.K.’s Housing Crisis

Addressing the U.K. housing shortage will require a multifaceted, strategic approach, recognising the urgent need for land to accommodate new homes and infrastructure.

Blog

Mexico City Is Reckoning With Explosive Economic Growth Alongside a Mounting Water Crisis

Despite an influx of capital and accelerated economic growth, Mexico City is grappling with a water shortage and affordability challenges.

Blog

Ecological Urbanism Is the Future for Cities in the GCC

As more people move to urban areas, it is essential that our urban spaces be designed in a more ecological manner.

Research

Redefining the Future of Urban Wellness in China

We created a framework and adaptable urban design toolkit to promote wellness in Chinese cities at the neighborhood level.

Blog

Equity and Aging in the 20-Minute City

By designing spaces that prioritize universal design principles and connectivity, we can create more accessible, purposeful places for seniors.

Blog

Libraries Are Crucial Social Infrastructure for the 20-Minute City

Once known solely as places for books, libraries are pivoting and adapting to adopt new roles in society.

Blog

Gensler’s City Pulse Retrospective Tracks the Complex Shifts in Urban Life

Our latest cities research reveals that despite pain points, the desirability of cities persists.

Podcast

The Future of Downtown Is the Lifestyle District

We explore lifestyle districts and how we can design the future of downtowns to respond to people’s evolving needs and experiences through new best...

Research

Designing Food-Resilient Cities

We researched how designers can reimagine food production to cities to better connect residents to their food and foster a food-resilient future.

Blog

Why Connected Neighborhoods Are Key to Urban Revitalization

In cities like Nashville, new development must consider the need to enhance neighborhood character and a connected urban experience.

Blog

Equity and the 20-Minute Neighborhood

To build stronger, more resilient, and equitable communities it’s essential that we leverage the power of research and engage residents.

FEATURED CITIES PROJECTS

Avon Lake Renewable Master Plan

Avon Lake, Ohio

Gensler worked in collaboration with the City of Avon Lake and ALERG to reposition the site of a recently decommissioned coal-fired power plant.

Fleet Street Quarter Public Realm Strategy

London, United Kingdom

Gensler has been working closely with Fleet Street Quarter BID, the City of London, and key stakeholders and businesses to define a vision to create a sustai...

Reimagining North Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois

Gensler and a team of key real estate leaders studied the innovations and interventions that could elevate the North Michigan Avenue experience.

CITIES & URBAN DESIGN NEWS

-

Gensler Press Release

2025New Research from Gensler Unveils the Magnetic Forces Shaping Cities — and Why People Choose to Stay -

Bloomberg CityLab

2025Bloomberg CityLab interviewed Gensler leaders about how cities can attract new residents, particularly young people and families, by converting office buildings into new housing to revive downtowns. -

Challenger Cities

2025Challenger Cities featured Gensler Global Cities Research Lead Sofia Song on a podcast about “The Magnetic, Messy Cities People Don’t Leave.” The discussion was anchored by Gensler’s City Pulse Survey findings, which delve into what makes cities not just livable — but lovable.

Interested in working with us?