Cities & Urban Design

Baghdad Sustainable Forests

Wichita State University Campus Master Plan

Northside Forward

Avenue of the Arts

Confidential Mixed Use Master Plan

The Crossing at University of Kansas Master Plan

Reimagining North Michigan Avenue

Harborplace

Fleet Street Quarter Public Realm Strategy

Right to Dream Ghana

Avon Lake Renewable Master Plan

Amtrak – Baltimore Penn Station Lanvale Expansion

Englewood Agro-Eco District

The AVE

Black Ensemble Theater

Haizhu Innovation Bay

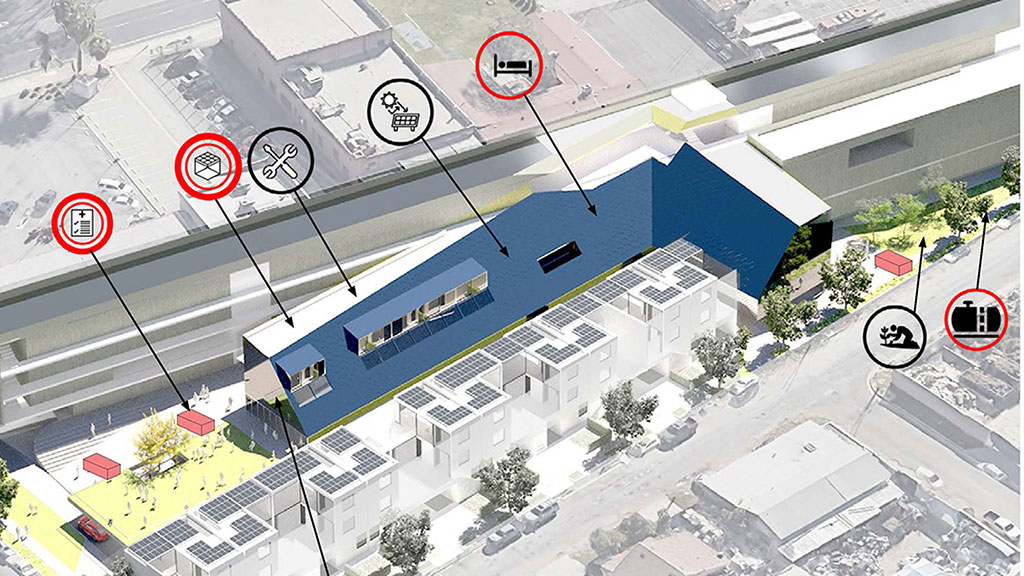

El Monte Busway and Transit Pavilion

Western Kentucky University

Campus Master Plan

University of Tasmania Urban Precincts Master Plan

205 Feddan

First Creek Redevelopment Plan

Southtown Redevelopment Plan

Citadel Mall Redevelopment Plan

Peña Station Transit-Oriented Development Plan

Hollywood Boulevard Walk of Fame Streetscape

Corferias 2030

Southbridge Redevelopment Plan

Urban Design & Master Planning

From new cities to urban districts to individual blocks, we design places that connect people. Our urban design plans balance public realm, vertical development, and complex urban systems. We work with developers, public agencies, non-governmental organizations, and institutions at all stages, from vision plans and feasibility studies to entitlements and implementation.

Transit & Mobility Planning

Our clients include public transit agencies, developers, and public-private partnerships delivering major infrastructure projects and transit facilities. We bring deep expertise in transit-oriented and multimodal development and believe that new and alternative mobility strategies can influence how we plan for the next generation.

Special District & Campus Planning

We offer specialized expertise in projects involving sports, entertainment, retail, and educational facilities to anchor urban districts and catalyze development. We work with economic development agencies, professional sports teams, universities, and developers to create compelling and functional plans for transformational projects.

Long-Range & Strategic Planning

We assist municipalities and institutions in setting long-range visions and policies that guide development for the future of our cities. Our planners and strategists are experts in the public process, with experience in stakeholder engagement and facilitation.

Neighborhood Planning

We believe in equitable neighborhoods that provide access to opportunity and choice. With a sensitive approach towards the unique scale of neighborhoods, we plan thriving and cohesive places to live. We work directly with public agencies and community organizations to create unique stakeholder-driven plans that prioritize residents’ needs, honor the past, and look to the future.

Affordable Housing

We recognize that many of our global cities are facing a housing crisis and take an active role in ensuring housing for all. Our team offers experience planning and designing affordable urban housing solutions for all income levels.

City Pulse 2025

How Privately Owned Public Spaces Can Impact Your Social Health

Equitable Urbanism

Advancing Equity in Latin America’s Built Environment

For People to Stay, They Need Places to ‘Go’

Inside Bangalore’s Talent Race: The Power of Purposeful Workplace Design

San Francisco’s AI Boom Is Our Chance to Build a People-First City

Age-Welcoming Cities: Designing for an Era of Longevity

Birmingham Living: The Next Chapter

Designing German Cities and Workplaces for a Thriving Economy

Climate Change Is Threatening What We Love About Cities

Families Are Leaving Cities — Here’s How to Win Them Back

Unlocking the Power of Forgotten Space to Combat Loneliness

The Top 10 Cities People Don’t Want to Leave

How Cities Can Establish Resilient Communities

The 20 Cities Attracting the Most Newcomers

Cities emerge as hubs for multidisciplinary innovation.

The growing scale and complexity of urban challenges mandate deep interdisciplinary collaboration. Cities are increasingly shaped by teams that blend architecture, landscape, mobility, resilience, and data science, creating integrated solutions for urban challenges.

The global housing crisis accelerates urban reinvention.

Affordable, high-quality housing is the defining challenge for cities of all sizes in both developed and emerging economies. Cities build more housing units and repair the urban fabric by redeveloping underused land in both the urban core and city’s edge. This reintegrates divided neighborhoods and creates equitable social infrastructure.

Climate migration reshapes the future of urban life.

Climate change defines future relocation patterns, turning some cities into sanctuaries, and threatening others with population decline. Resilience is at the top of the new urban agenda: creating places that can absorb shocks, protect residents, welcome newcomers, and prepare for a rapidly shifting climate.

Andre Brumfield

Ian Mulcahey

Christopher Rzomp

Dylan Jones

Gensler Cities & Urban Design Global Leader Andre Brumfield Shares Insights on the Future of Urban Development

Gensler Co-CEOs Join “I Hear Design” Podcast to Share Key Takeaways From 2026’s Design Forecast

Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 Reveals the Cities With High Shares of Young Adults Who Are Thinking About Leaving

Axios Highlights U.S. City Resident Satisfaction Rates with Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 Survey Findings

Diane Hoskins Joins Real Estate Capital Podcast to Discuss How Design, Research, and Mobility Are Transforming Cities

Challenger Cities Featured Gensler’s Sofia Song on a Podcast About “The Magnetic, Messy Cities People Don’t Leave”

How Gensler Transformed a Decommissioned Power Plant into an Award-Winning Lakefront Destination

BBC Radio London Interviewed Cities & Urban Design Leader Ian Mulcahey About Gensler’s 2025 City Pulse Survey

Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 Reveals That While Affordability Draws People to Cities, Emotional Connection Keeps Them There

Design Middle East Highlights Gensler’s City Pulse 2025 with Insights on UAE Urban Life

Creative Mornings Hosted a Talk With Gensler Strategy Director Brian Stromquist on Reviving Cities

Property Week Explores Approaches for Redefining Retrofit

NLA and Gensler’s Michaela Winter-Taylor Explored Fleet Street’s Legacy of Innovation

Baltimore Sun Announced That Gensler Will Lead the Baltimore Harborplace Redevelopment